The post Elevate Your Contact Center Experience with Krisp Background Voice Cancellation (BVC) appeared first on Krisp.

]]>What is Krisp Background Voice Cancellation?

Krisp BVC is an advanced AI noise-canceling technology that eliminates all background noises and other competing voices nearby, including the voices of other agents. This breakthrough technology is enabled as soon as an agent plugs in their headsets, without requiring individual voice enrollment or training. This innovative solution integrates smoothly with both native applications and browser-based calling applications via WebAssembly JavaScript (WASM JS), ensuring high performance and efficiency.

Why Choose Krisp BVC for Your Contact Center?

1. Enhanced Customer Experience

Customers often struggle with understanding agents when there’s background chatter, leading to frustration and reduced satisfaction. By using Krisp BVC, all extraneous voices and noises are filtered out, allowing customers to focus solely on the agent they are speaking with. This ensures a smooth and professional interaction every time, which directly contributes to higher CSAT scores.

2. Privacy and Confidentiality

In a contact center, the risk of customers overhearing personal information from other calls is a significant concern, especially for financial and healthcare customers. Krisp BVC addresses this by completely isolating the agent’s voice from the background, ensuring that sensitive information remains confidential.

3. Hardware Independence

While headsets and other hardware solutions provide some noise reduction, they do not eliminate background voices. Krisp BVC works independently of hardware, offering superior noise and background voice cancellation without the need for additional devices or complicated setups.

4. Plug-and-Play Functionality

Once the agent’s headset is plugged in, Krisp BVC is activated automatically. There’s no need for agents to enroll their voice or go through any training process, making it an effortless solution that saves time and resources.

5. Versatility Across Platforms

Krisp BVC is uniquely available for both native applications and browser-based calling applications through WASM JS. This means it can be integrated effortlessly into various platforms, ensuring consistent performance and reliability.

6. Efficient Performance

Krisp BVC is designed to run efficiently in the browser, making it an ideal solution for Contact Center as a Service (CCaaS) platforms. Its high-performance capabilities ensure minimal latency and a smooth user experience.

7. Improved CSAT Metrics

With the enhanced clarity of communication provided by Krisp BVC, customers are more likely to have positive interactions with agents. This leads to increased satisfaction, as reflected in improved CSAT metrics reported to us by a number of customers. Clear and effective communication is crucial in resolving issues promptly and accurately, which in turn boosts customer loyalty and satisfaction.

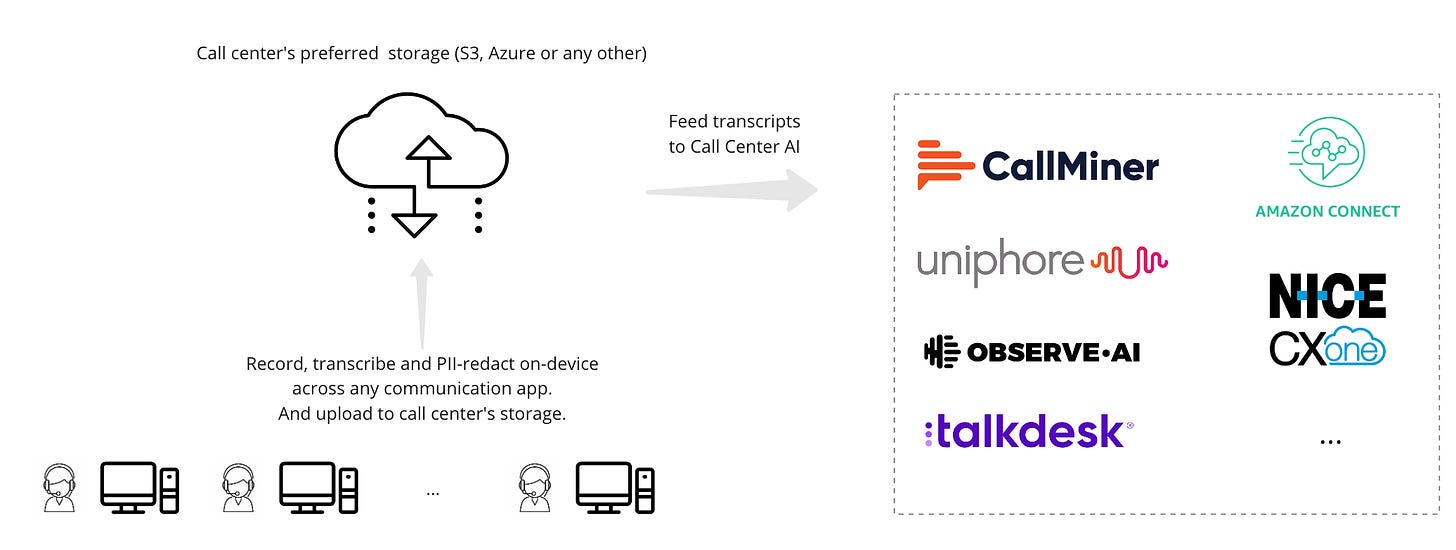

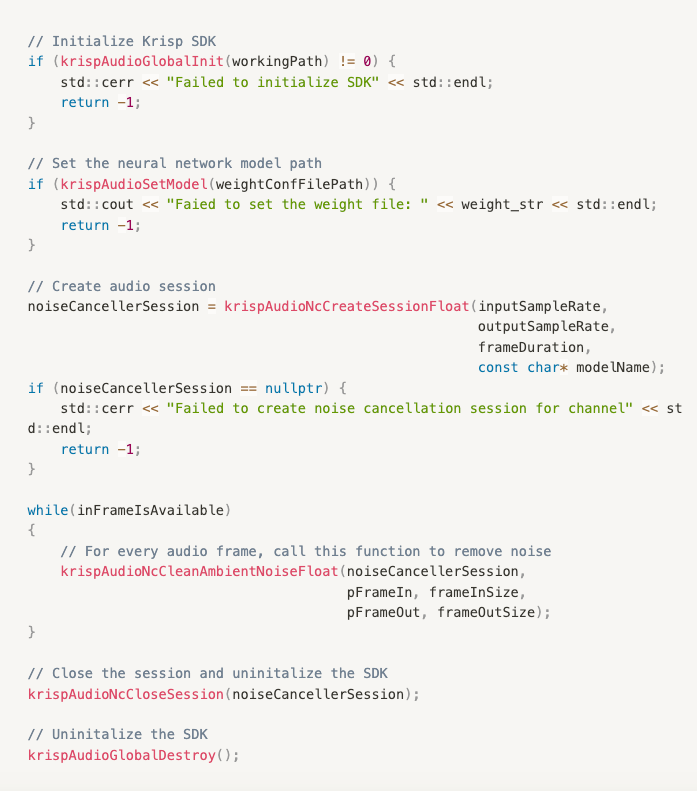

Integration Made Easy

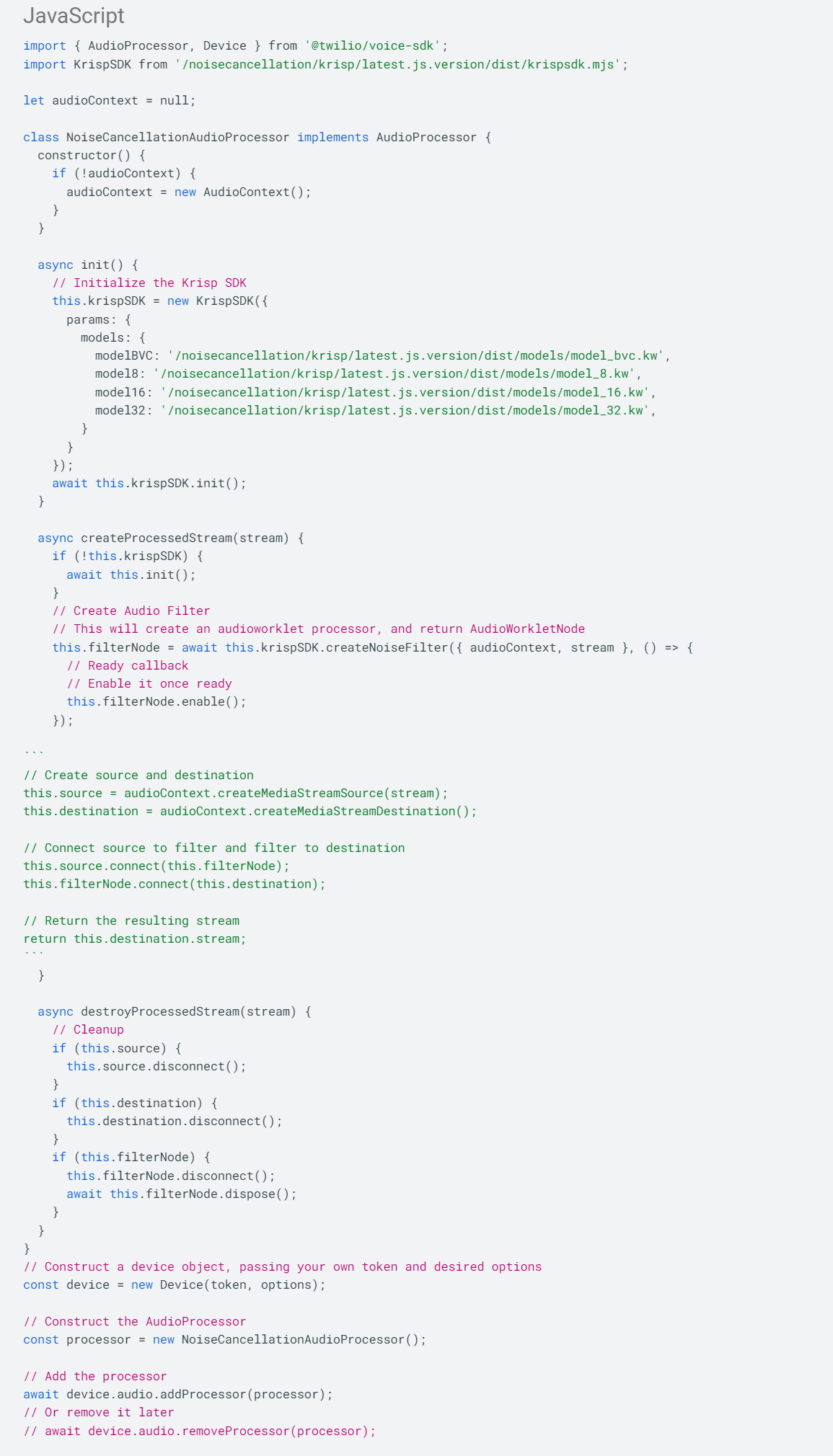

Integrating Krisp BVC into your contact center application is straightforward. Here’s a sample code snippet to demonstrate how simple it is to get started:

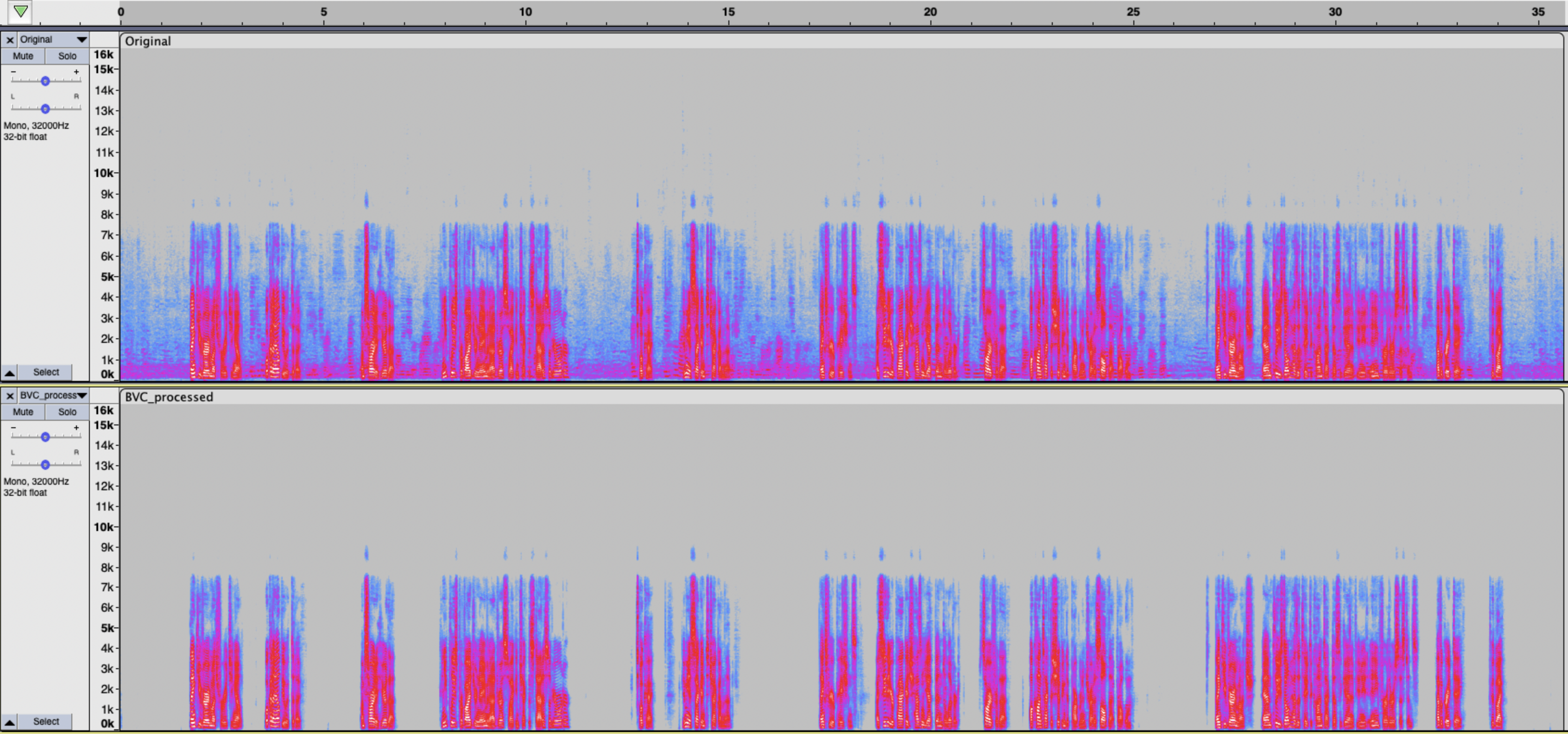

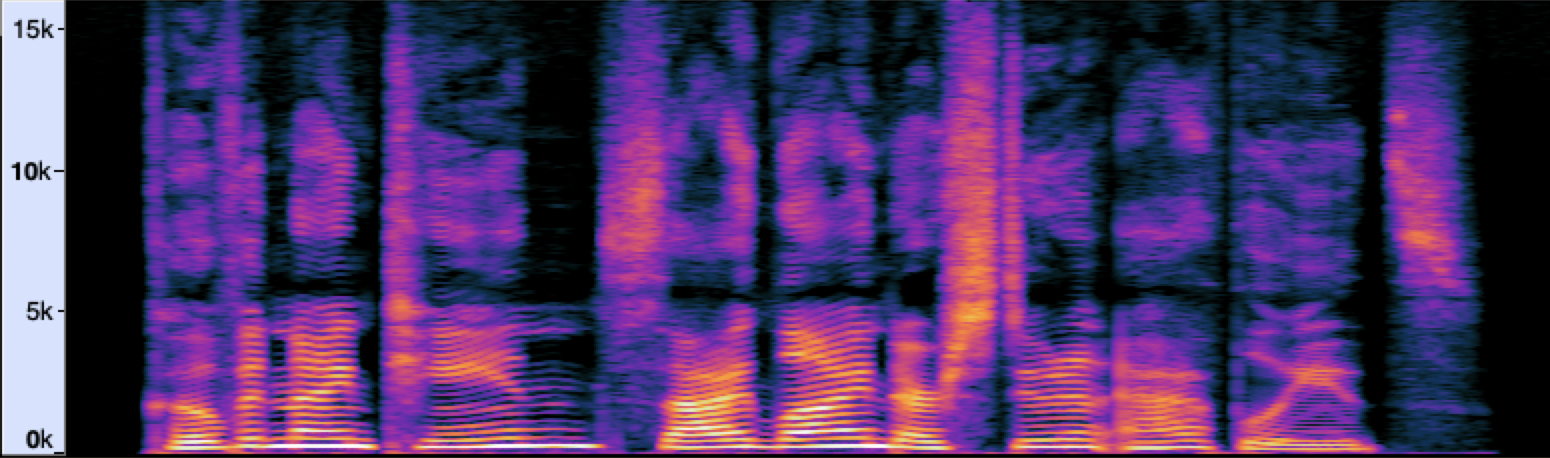

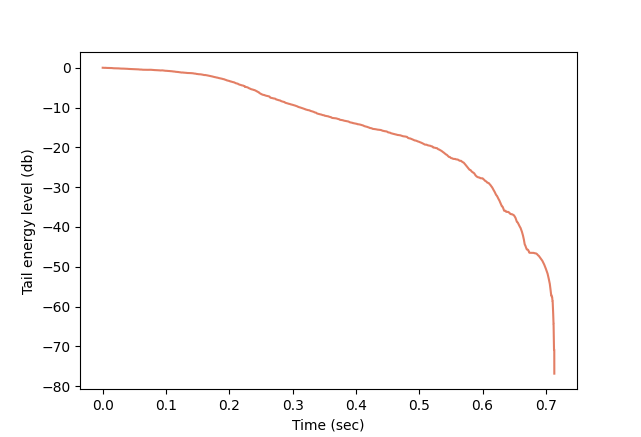

Visualizing the Difference

The graphical representation above illustrates the clarity and focus achieved by using Krisp BVC. Notice how the agent’s speech is clear and distinct, free from background distractions.

Hear the Difference

Experience the transformative power of Krisp BVC with this audio comparison:

Without BVC – Competing Agent Voices

With BVC – Clear communication

Conclusion

Integrating Krisp BVC into your contact center solutions can significantly enhance the quality of interactions and customer satisfaction. Its ease of integration, combined with superior performance and versatility, makes Krisp BVC a must-have feature for modern contact centers. Upgrade your communication systems today with Krisp Background Voice Cancellation and experience the difference it makes, including improved CSAT metrics.

Ready to get started? Visit Krisp’s Developer Portal for more information and comprehensive integration guides.

The post Elevate Your Contact Center Experience with Krisp Background Voice Cancellation (BVC) appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post Enhancing Browser App Experiences: Krisp JS SDK Pioneers In-browser AI Voice Processing for Desktop and Mobile appeared first on Krisp.

]]>In today’s connected world, where web browsers serve as gateways to an assortment of online experiences, ensuring a seamless and productive user experience is paramount. One crucial aspect often overlooked in browser-based communication applications is voice quality, especially in scenarios where clarity of communication is essential.

Diverse Applications of Noise Cancellation on the Web

From virtual meetings and online classes to contact center operations, the demand for clear audio communications has become ever more important, making AI Voice processing with noise and background voice cancellation an expected and highly sought-after feature. While standalone applications have provided this functionality, integrating this directly into browser-based applications has proven to be a challenge.

The need for noise and background voice cancellation extends beyond conventional communication platforms. In Telehealth, for instance, where accurate communication is vital for call-based diagnosis and consultation, background noise and voices can hinder effective communication. Another interesting example is insurance companies, taking calls from their customers from the place of an incident. Eliminating background noise ensures that critical information is accurately conveyed, leading to smoother claims processing and customer satisfaction. These, and many other use cases, often involve one-click web sessions for the calls.

Overcoming Challenges for Mobile Browser Integration

The growing demand for quality communications in browser-based applications extends to both desktop and mobile devices. Up until recently, achieving compatibility with mobile devices, particularly with iOS Safari, posed significant difficulties. Limitations within Apple’s WebKit framework and the inherently CPU-intensive nature of JavaScript solutions hindered bringing the power of Krisp’s technologies to mobile browser applications.

The introduction of Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) support marked a significant opening for Krisp to deliver its market-leading technology into Safari specifically, and mobile browsers generally. SIMD enables parallel processing of data, significantly boosting performance and efficiency, particularly on mobile devices with limited computational resources.

By leveraging SIMD, the Krisp JS SDK has achieved low levels of CPU efficiency, making its market-leading noise cancellation available for users on mobile browser applications. This breakthrough not only enhances the user experience but also opens up new possibilities for web-based applications across various industries.

As Krisp’s technologies continue to evolve and extend into new territories, the ability to make AI Voice features available for all users across desktop and mobile browser-based applications is fundamental and allows users to have seamless access to the best voice processing technologies in the market.

Try next-level audio and voice technologies

Krisp licenses its SDKs to embed directly into applications and devices. Learn more about Krisp’s SDKs and begin your evaluation today.

The post Enhancing Browser App Experiences: Krisp JS SDK Pioneers In-browser AI Voice Processing for Desktop and Mobile appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post Krisp Delivers AI-Powered Voice Clarity to Symphony’s Trader Voice Products appeared first on Krisp.

]]>BERKELEY, Calif., April 17, 2024 – Krisp, the world’s leading AI-powered voice productivity software, announced today a new integration with Symphony’s trader voice platform, Cloud9, to enhance voice audio clarity. The partnership delivers Krisp’s advanced AI Noise Cancellation, enabling Cloud9 users to experience clear audio in challenging environments, such as trading floors and busy offices.

Through the integration, Symphony will also be able to enhance its built-for-purpose financial markets voice analytics in partnership with Google Cloud. By creating a space of uninterrupted audio between counterparties both on and off of Cloud9, more efficient communication is allowed with fewer disagreements. Accurate transcription of audio recordings is enhanced with compliance review in mind.

“We are thrilled to partner with Symphony and integrate our Voice AI technology into their products,” said Robert Schoenfield, EVP of Licensing and Partnerships at Krisp. “Symphony’s customers operate in difficult noisy environments, dealing with high value transactions. Improving their communication is of real value.”

Symphony’s chief product officer, Michael Lynch, said: “Cloud9 SaaS approach to trader voice gives our users the flexibility to work from anywhere, whether it’s a bustling trading desk or their living room, and KRISP improves our already best-in-class audio quality to help our users make the best possible real-time decisions while also improving post-trade analytics and compliance.”

This collaboration not only brings improved communication quality but also aligns with Krisp’s and Symphony’s commitment to bringing industry-leading solutions to their customers.

About Krisp

Founded in 2017, Krisp pioneered the world’s first AI-powered Voice Productivity software. Krisp’s Voice AI technology enhances digital voice communication through audio cleansing, noise cancelation, accent localization, and call transcription and summarization. Offering full privacy, Krisp works on-device, across all audio hardware configurations and applications that support digital voice communication. Today, Krisp processes over 75 billion minutes of voice conversations every month, eliminating background noise, echoes, and voices in real-time, helping businesses harness the power of voice to unlock higher productivity and deliver better business outcomes.

Learn more about Krisp’s SDK for developers.

Press contact:

Shara Maurer

Head of Corporate Marketing

[email protected]

About Symphony

Symphony is the most secure and compliant markets’ infrastructure and technology platform, where solutions are built or integrated to standardize, automate and innovate financial services workflows. It is a vibrant community of over half a million financial professionals with a trusted directory and serves over 1000 institutions. Symphony is powering over 2,000 community built applications and bots. For more information, visit www.symphony.com.

Press contact:

Odette Maher

Head of Communications and Corporate Affairs

+44 (0) 7747 420807 / [email protected]

The post Krisp Delivers AI-Powered Voice Clarity to Symphony’s Trader Voice Products appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post Twilio Partners with Krisp to Provide AI Noise Cancellation to All Twilio Voice Customers appeared first on Krisp.

]]>How Krisp AI Noise Cancellation works

Trusted by more than 100 million users to process over 75 billion minutes of calls monthly, Krisp’s Voice AI SDKs are designed to identify human voice and cancel all background noise and voices to eliminate distractions on calls. Krisp SDKs are available for browsers (WASM JS), desktop apps (Win, Mac, Linux) and mobile apps (ioS, Android.) The Krisp Audio Plugin for Twilio Voice is a lightweight audio processor that can run inside your client application and create crystal clear audio.

The plugin needs to be loaded alongside the Twilio SDK and runs as part of the audio pipeline between the microphone and audio encoder in a preprocessing step. During this step, the AI-based noise cancellation algorithm removes unwanted sounds like barking dogs, construction noises, honking horns, coffee shop chatter and even other voices.

After the preprocessing step, the audio is encoded and delivered to the end user. Note that all of these steps happen on device, with near zero latency and without any media sent to a server.

Requirements and considerations

Krisp’s AI Noise Cancellation requires you to host and serve the Krisp audio plugin for Twilio Voice as part of your web application. It also requires browser support of the WebAudio API (specifically Worklet.addModule). Krisp has a team ready to support your integration and optimization for great voice quality.

Learn more about Krisp here and apply for access to the world’s best Voice AI SDKs.

Get started with AI Noise Cancellation

Visit the Krisp for Twilio Voice Developers page to request access to the Krisp SDK Portal. Once access is granted, download Krisp Audio JS SDK and place it in the assets of your project. Use the following code snippet to integrate the SDK with your project. Read the comments inside the code snippets for additional details.

Visit Krisp for Twilio Voice Developers and get started today.

The post Twilio Partners with Krisp to Provide AI Noise Cancellation to All Twilio Voice Customers appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post On-Device STT Transcriptions: Accurate, Secure and Less Expensive appeared first on Krisp.

]]>

The on-device requirement has in many ways shaped the technical specifications of the technology and posed a series of challenges that the team has been able to tackle head-on, working through various iterations. The path to achieving high quality on-device STT continues, as the Krisp app has now transcribed over 15 million hours of calls and the company is now making this technology for its license partners via on-device SDKs. Let’s dive into the specific challenges Krisp worked through to bring this technology to market.

Challenges and solutions to on-device STT

Resource constraints

Without diving into the specifics of on-device STT technology and its architecture, one of the first and obvious constraints that the development had to be guided by was the computational resource. On-device STT systems operate within the confines of limited resources, including CPU, memory, and power. Unlike cloud-based solutions, which can leverage expansive server infrastructure, on-device systems must deliver comparable performance with significantly restricted resources. This constraint necessitates the optimization of algorithms, models, and processing pipelines to ensure efficient resource utilization without compromising accuracy and responsiveness. In many use cases, STT would need to run alongside the Noise Cancellation and other technologies, which further impacts the overall available bandwidth of resources.

Model complexity and size

The effectiveness of STT models hinges on their complexity and size, with larger models generally exhibiting superior accuracy and robustness. However, deploying large models on-device presents a formidable challenge, as it exacerbates memory and processing overheads. Balancing model complexity and size becomes paramount, requiring developers to employ techniques like model pruning, quantization, and compression to achieve optimal trade-offs between performance and resource utilization.

In order to achieve high quality transcripts and feature-rich speech-to-text systems, there is a need to build complex network architectures consisting of a number of AI models and algorithms. Such models include language models, punctuation and text normalization, speaker diarization and personalization (custom vocabulary) models, each presenting unique technical challenges and performance considerations.

The technology that Krisp employs both in its app and SDKs includes a combination of all of the above-mentioned technologies, as well as other adjacent algorithms to ensure readability and grammatical coherence of the final output.

The language model enhances transcription accuracy by predicting the likelihood of word sequences based on contextual and syntactic information. It helps in disambiguating words and improving the coherence of transcribed text. The Punctuation & Capitalization Model predicts the appropriate punctuation marks and capitalization based on speech patterns and semantic cues, enhancing the readability and comprehension of transcribed text. While the Inverse Text Normalization model standardizes and formats transcribed text to adhere to predefined conventions, such as converting numbers to textual representations or vice versa, expanding abbreviations, and correcting spelling errors. For cases where customers might have domain-specific terminology or proper names that are not widely recognized by the standard models, Krisp also provides Custom Vocabulary support.

Apart from the features ensuring text readability and accuracy, a major important technology included in Krisp’s on-device STT is Speaker Diarization. This model segments speech into distinct speaker segments, enabling the identification and differentiation of multiple speakers within a conversation or audio stream. It is crucial for speaker-dependent processing and improving transcription accuracy in multi-speaker scenarios.

Real or near real-time processing for on-device STT

Depending on a use case, on-device STT technology might have to deliver real or near real-time processing capabilities to enable seamless user interactions across diverse applications. Achieving low-latency speech recognition necessitates streamlining inference pipelines, minimizing computational overheads, and optimizing signal processing algorithms. Moreover, the heterogeneity of device architectures and hardware accelerators further complicates real-time performance optimization, requiring tailored solutions for different platforms and configurations. Krisp developers have achieved a delicate balance between latency, selecting optimal model combinations, ensuring processing synergy, and addressing the scalability and flexibility of the pipeline to accommodate various use-cases.

Robustness to variability

With a global and multi-domain user-base, there is an inherent variability of speech arising from diverse accents, vocabularies, environments, and speaking styles. Our on-device STT technology must exhibit robustness to such variability to ensure consistent performance across disparate contexts. This entails training models on diverse datasets, augmenting training data to encompass various scenarios, and implementing robust feature extraction techniques capable of capturing salient speech characteristics while mitigating noise and various device or network-dependent distortions.

In addition to addressing resource constraints and optimizing algorithms for on-device STT, Krisp prioritizes rigorous speech recognition testing to ensure its technology’s robustness across diverse accents, environments, and speaking styles.

Integration & embeddability of on-device STT

Along with being on-device, the technologies underlying the Krisp app AI Meeting Assistant are also designed with embeddability in mind. Integrating on-device STT technology into communication applications and devices presents a range of additional challenges, all of which Krisp has tackled. Resources must be carefully allocated to ensure optimal performance without compromising existing customer infrastructure. Customization and configuration options are essential to meet the diverse needs of end-users while maintaining scalability and performance across large-scale deployments. Security and compliance considerations demand robust encryption and privacy measures to protect sensitive data. Seamless integration with existing infrastructure, including telephony systems and collaboration tools, requires interoperability standards, codec support and integration frameworks.

One prevailing requirement for communication services is for on-device STT technology to be functional on the web. This presents a new set of challenges in terms of further resource optimization, as well as compatibility across diverse web platforms, browsers, frameworks and devices.

Bringing it all together

While the integration of on-device STT technology into communication applications and devices presents challenges and requires meticulous resource utilization, customization, and seamless interoperability, Krisp has addressed these challenges and today delivers embedded STT solutions that enhance the functionality and value proposition for applications and their end-users.

Try next-level on-device STT, audio and voice technologies

Krisp licenses its SDKs to embed directly into applications and devices. Learn more about Krisp’s SDKs and begin your evaluation today.

The post On-Device STT Transcriptions: Accurate, Secure and Less Expensive appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post Deep Dive: AI’s Role in Accent Localization for Call Centers appeared first on Krisp.

]]>

Accent refers to the distinctive way in which a group of people pronounce words, influenced by their region, country, or social background. In broad terms, English accents can be categorized into major groups such as British, American, Australian, South African, and Indian among others.

Accents can often be a barrier to communication, affecting the clarity and comprehension of speech. Differences in pronunciation, intonation, and rhythm can lead to misunderstandings.

While the importance of this topic goes beyond call centers, our primary focus is this industry.

Offshore expansion and accented speech in call centers

The call center industry in the United States has experienced substantial growth, with a noticeable surge in the creation of new jobs from 2020-onward, both on-shore and globally.

In 2021, many US based call centers expanded their footprints thanks to the pandemic-fueled adoption of remote work, but growth slowed substantially in 2022. Inflated salaries and limited resources drove call centers to deepen their offshore operations, both in existing and new geographies.

There are several strong incentives for businesses to expand call centers operations to off-shore locations, including:

- Cost savings: Labor costs in offshore locations such as India, the Philippines, and Eastern Europe are up to 70% lower than in the United States.

- Access to diverse talent pools: Offshoring enables access to a diverse talent pool, often with multilingual capabilities, facilitating a more comprehensive customer support service.

- 24/7 coverage: Time zone differences allow for 24/7 coverage, enhancing operational continuity.

However, offshore operations come with a cost. One major challenge offshore call centers face is decreased language comprehension. Accents, varying fluency levels, cultural nuances and inherent biases lead to misunderstandings and frustration among customers.

According to Reuters, as many as 65% of customers have cited difficulties in understanding offshore agents due to language-related issues. Over a third of consumers say working with US-based agents is most important to them when contacting an organization.

Ways accents create challenges in call centers

While the world celebrates global and diverse workforces at large, research shows that misalignment of native language backgrounds between speakers leads to a lack of comprehension and inefficient communication.

- Longer calls: Thick accents contribute to comprehension difficulties, causing higher average handle time (AHT) and also lower first call resolutions (FCR).

According to ContactBabel’s “2024 US Contact Center Decision Maker’s Guide” the cost of mishearing and repetition per year for a 250-seat contact center exceeds $155,000 per year.

- Decreased customer satisfaction: Language barriers are among the primary contributors to lower customer satisfaction scores within off-shore call centers. According to ContactBabel, 35% of consumers say working with US-based call center agents is most important to them when contacting an organization.

- High agent attrition rates: Decreased customer satisfaction and increased escalations create high stress for agents, in turn decreasing agent morale. The result is higher employee turnover rates and short-term disability claims. In 2023, US contact centers saw an average annual agent attrition rate of 31%, according to The US Contact Center Decision Makers’ Guide to Agent Engagement and Empowerment.

- Increased onboarding costs: The need for specialized training programs to address language and cultural nuances further adds to onboarding costs.

- Limited talent pool: Finding individuals who meet the required linguistic criteria within the available talent pool is challenging. The competitive demand for specialized language skills leads to increased recruitment costs.

How do call centers mitigate accent challenges today?

Training

Accent neutralization training is used as a solution to improve communication clarity in these environments. Call Centers invest in weeks-long accent neutralization training as part of agent onboarding and ongoing improvement. Depending on geography, duration, and training method, training costs can run $500-$1500 per agent during onboarding. The effectiveness of these training programs can be limited due to the inherent challenges in altering long-established accent habits. So, call centers may find it necessary to temporarily remove agents from their operational roles for further retraining, incurring additional costs in the process.

Limited geography for expansion

Call centers limit their site selection to regions and countries where accents of the available talent pool is considered to be more neutral to the customer’s native language, sacrificing locations that would be more cost-effective.

Enter AI-Powered Accent Localization

Recent advancements in Artificial Intelligence have introduced new accent localization technology. This technology leverages AI to translate source accents to targets accent in real-time, with the click of a button. While the technologies in production don’t support multiple accents in parallel, over time this will be solved as well.

State of the Art AI Accent Localization Demo

Below is the evolution of Krisp’s AI Accent Localization technology over the past 2 years.

| Version | Demo |

|---|---|

| v0.1 First model | |

| v0.2 A bit more natural sound | |

| v0.3 A bit more natural sound | |

| v0.4 Improved voice | |

| v0.5 Improved intonation transfer |

This innovation is revolutionary for call centers as it eliminates the need for difficult and expensive training and increases the talent pool worldwide, providing immediate scalability for offshore operations.

It’s also highly convenient for agents and reduces the cognitive load and stress they have today. This translates to decreased short-term disability claims and attrition rates, and overall improved agent experience.

Deploying AI Accent Localization in the call center

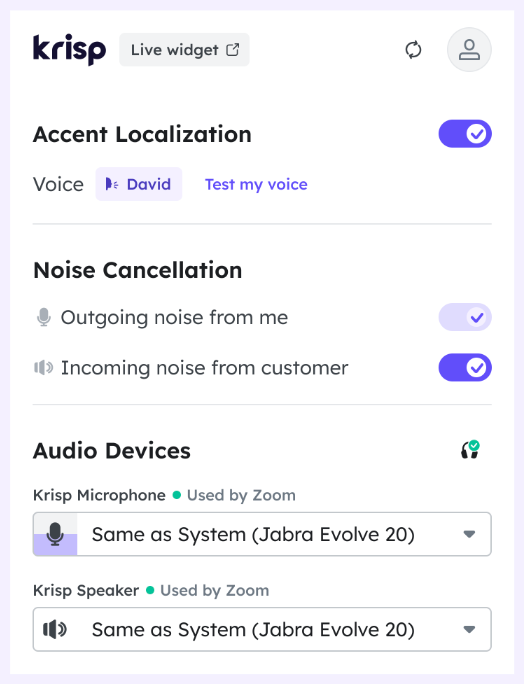

There are various ways AI Accent Localization can be integrated into a call center’s tech stack.

It can be embedded into a call center’s existing CX software (e.g. CCaaS and UCaaS) or installed as a separate application on the agent’s machine (e.g. Krisp).

Currently, there are no CX solutions in market with accent localization capabilities, leaving the latter as the only possible path forward for call centers looking to leverage this technology today.

Applications like Krisp have accent localization built in their offerings.

These applications are on-device, meaning they sit locally on the agent’s machine. They support all CX software platforms out of the box since they are installed as a virtual microphone and speaker.

AI runs on an agent’s device so there is no additional load on the network.

The deployment and management can be done remotely, and at scale, from the admin dashboard.

Challenges of building AI Accent Localization technology

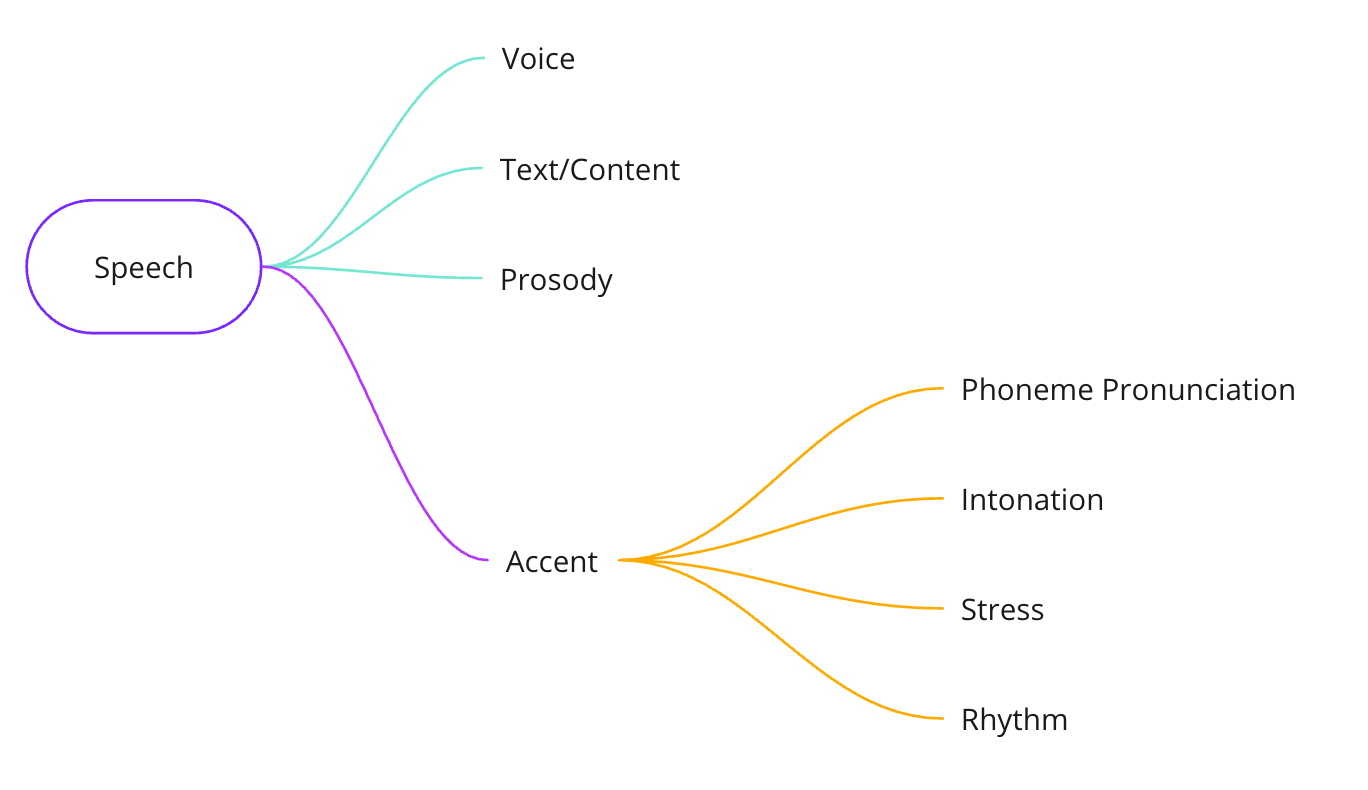

At a fundamental level, speech can be divided into 4 parts: voice, text, prosody and accent.

Accents can be divided into 4 parts as well – phoneme, intonation, stress and rhythm.

In order to localize or translate an accent, three of these parts must be changed – phoneme pronunciation, intonation, and stress. Doing this in real-time is an extremely difficult technical problem.

While there are numerous technical challenges in building this technology, we will focus on eight majors.

- Data Collection

- Speech Synthesis

- Low Latency

- Background Noises and Voices

- Acoustic Conditions

- Maintaining Correct Intonation

- Maintaining Speaker’s Voice

- Wrong Pronunciations

Let’s discuss them individually.

1) Data collection

Collecting accented speech data is a tough process. The data must be highly representative of different dialects spoken in the source language. Also, it should cover various voices, age groups, speaking rates, prosody, and emotion variations. For call centers, it is preferable to have natural conversational speech samples with rich vocabulary targeted for the use case.

There are two options: buy ready data or record and capture the data in-house. In practice, both can be done in parallel.

An ideal dataset would consist of thousands of hours of speech where source accent utterance is mapped to each target accent utterance and aligned with it accurately.

However, getting precise alignment is exceedingly challenging due to variations in the duration of phoneme pronunciations. Nonetheless, improved alignment accuracy contributes to superior results.

2) Speech synthesis

The speech synthesis part of the model, which is sometimes referred to as the vocoder algorithm in research, should produce a high-quality, natural-sounding speech waveform. It is expected to sound closer to the target accent, have high intelligibility, be low-latency, convey natural emotions and intonation, be robust against noise and background voices, and be compatible with various acoustic environments.

3) Low latency

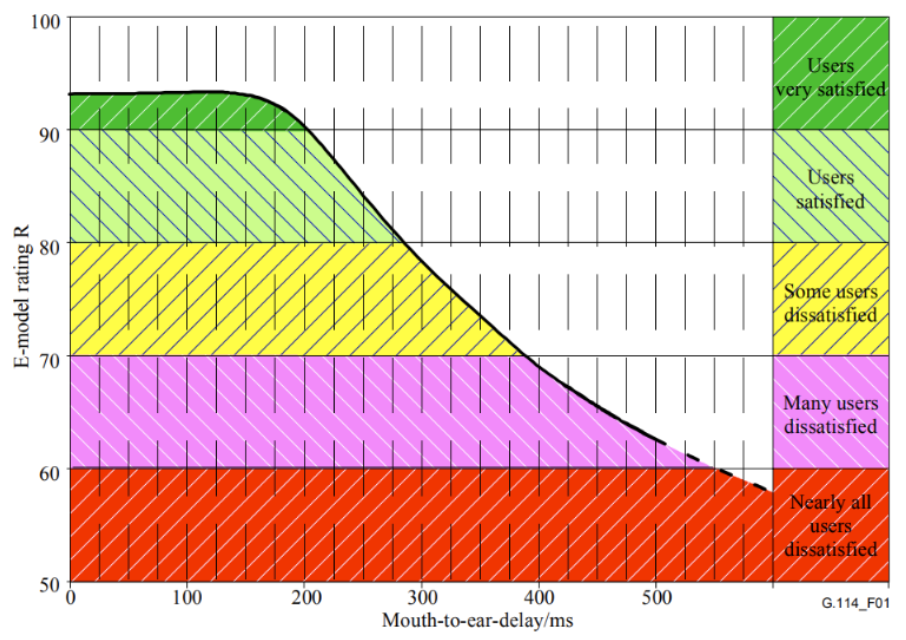

As studies by the International Telecommunication Union show (G.114 recommendation), speech transmission maintains acceptable quality during real-time communication if the one-way delay is less than approximately 300 ms. Therefore, the latency of the end-to-end accent localization system should be within that range to ensure it does not impact the quality of real-time conversation.

There are two ways to run this technology: locally or in the cloud. While both have theoretical advantages, in practice, more systems with similar characteristics (e.g. AI-powered noise cancellation, voice conversion, etc.) have been successfully deployed locally. This is mostly due to hard requirements around latency and scale.

To be able to run locally, the end-to-end neural network must be small and highly optimized, which requires significant engineering resources.

4) Background noise and voices

Having a sophisticated noise cancellation system is crucial for this Voice AI technology. Otherwise, the speech synthesizing model will generate unwanted artifacts.

Not only should it eliminate the input background noise but also the input background voices. Any sound that is not the speaker’s voice must be suppressed.

This is especially important in call center environments where multiple agents sit in close proximity to each other, serving multiple customers simultaneously over the phone.

Detecting and filtering out other human voices is a very difficult problem. As of this writing, to our knowledge, there is only one system doing it properly today – Krisp’s AI Noise Cancellation technology.

5) Acoustic conditions

Acoustic conditions differ for call center agents. The sheer volume of combinations of device microphones and room setups (accountable for room echo) makes it very difficult to design a robust system against such input variations.

6) Maintaining the speaker’s intonation

Not transferring the speaker’s intonation in the generated speech will result in a robotic speech that sounds worse than the original.

Krisp addressed this issue by developing an algorithm capturing input speaker’s intonation details in real-time and leveraging this information in the synthesized speech. Solving this challenging problem allowed us to increase the naturalness of the generated speech.

7) Maintaining the speaker’s voice

It is desirable to maintain the speaker’s vocal characteristics (e.g., formants, timbre) while generating output speech. This is a major challenge and one potential solution is designing the speech synthesis component so that it generates speech conditioned on the input speaker’s voice ‘fingerprint’ – a special vector encoding a unique acoustic representation of an individual’s voice.

8) Wrong pronunciations

Mispronounced words can be difficult to correct in real-time, as the general setup would require separate automatic speech recognition and language modeling blocks, which introduce significant algorithmic delays and fail to meet the low latency criterion.

3 technical approaches to AI Accent Localization

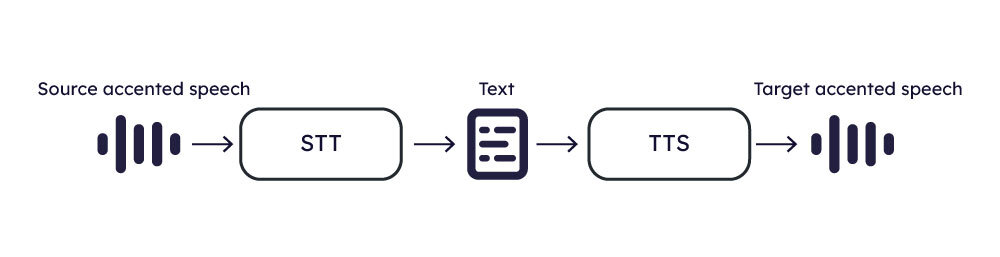

Approach 1: Speech → STT → Speech

One approach to accent localization involves applying Speech-to-Text (STT) to the input speech and subsequently utilizing Text-to-Speech (TTS) algorithms to synthesize the target speech.

This approach is relatively straightforward and involves common technologies like STT and TTS, making it conceptually simple to implement.

STT and TTS are well-established, with existing solutions and tools readily available.

Integration into the algorithm can leverage these technologies effectively. These represent the strengths of the method, yet it is not without its drawbacks. There are 3 of them:

- The difficulty of having accent-robust STT with a very low word error rate.

- The TTS algorithm must possess capabilities to manage emotions, intonation, and speaking rate, which should come from original accented input and produce speech that sounds natural.

- Algorithmic delay within the STT plus TTS pipeline may fall short of meeting the demands of real-time communication.

Approach 2: Speech → Phoneme → Speech

First, let’s define what a phoneme is. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a language that can distinguish words from each other. It is an abstract concept used in linguistics to understand how language sounds function to encode meaning. Different languages have different sets of phonemes; the number of phonemes in a language can vary widely, from as few as 11 to over 100. Phonemes themselves do not have inherent meaning but work within the system of a language to create meaningful distinctions between words. For example, the English phonemes /p/ and /b/ differentiate the words “pat” and “bat.”

The objective is to first map the source speech to a phonetic representation, then map the result to the target speech’s phonetic representation (content), and then synthesize the target speech from it.

This approach enables the achievement of comparatively smaller delays than Approach 1. However, it faces the challenge of generating natural-sounding speech output, and reliance solely on phoneme information is insufficient for accurately reconstructing the target speech. To address this issue, the model should also extract additional features such as speaking rate, emotions, loudness, and vocal characteristics. These features should then be integrated with the target speech content to synthesize the target speech based on these attributes.

Approach 3: Speech → Speech

Another approach is to create parallel data using deep learning or digital signal processing techniques. This entails generating a native target-accent sounding output for each accented speech input, maintaining consistent emotions, naturalness, and vocal characteristics, and achieving an ideal frame-by-frame alignment with the input data.

If high-quality parallel data are available, the accent localization model can be implemented as a single neural network algorithm trained to directly map input accented speech to target native speech.

The biggest challenge of this approach is obtaining high-quality parallel data.The quality of the final model directly depends on the quality of parallel data.

Another drawback is the lack of integrated explicit control over speech characteristics, such as intonation, voice, or loudness. Without this control, the model may fail to accurately learn these important aspects.

How to measure the quality AI Accent Localization output

High-quality output of accent localization technology should:

- Be intelligible

- Have little or no accentedness (the degree of deviation from the native accent)

- Sound natural

To evaluate these quality features, we use the following objective metrics:

- Word Error Rate (WER)

- Phoneme Error Rate (PER)

- Naturalness prediction

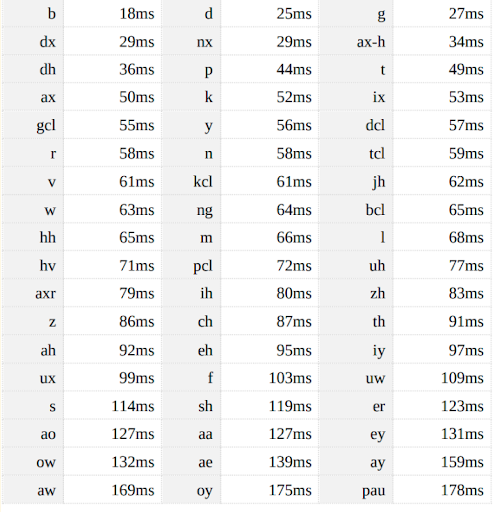

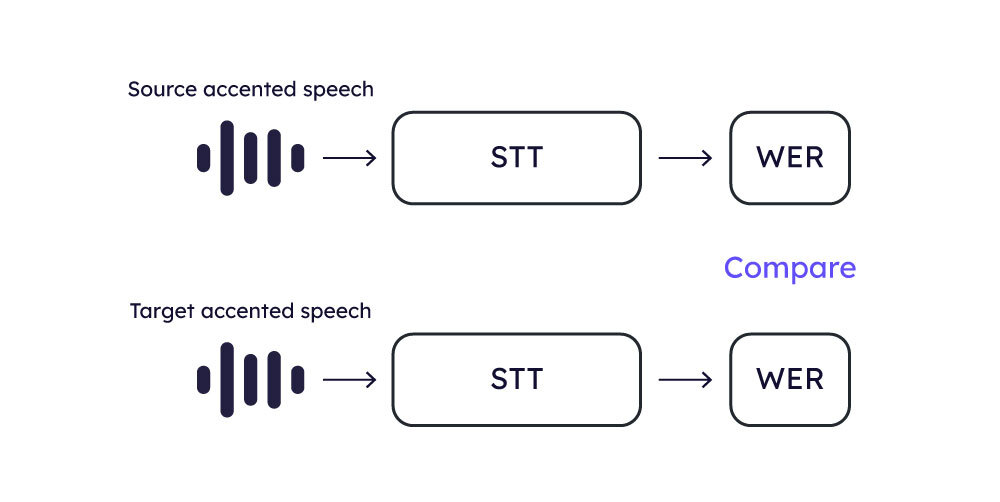

Word Error Rate (WER)

WER is a crucial metric used to assess STT systems’ accuracy. It quantifies the word level errors of predicted transcription compared to a reference transcription.

To compute WER we use a high-quality STT system on generated speech from test audios that come with predefined transcripts.

The evaluation process is the following:

- The test set is processed through the candidate accent localization (AL) model to obtain the converted speech samples.

- These converted speech samples are then fed into the STT system to generate the predicted transcriptions.

- WER is calculated using the predicted and the reference texts.

The assumption in this methodology is that a model demonstrating better intelligibility will have a lower WER score.

Phoneme Error Rate (PER)

The AL model may retain some aspects of the original accent in the converted speech, notably in the pronunciation of phonemes. Given that state-of-the-art STT systems are designed to be robust to various accents, they might still achieve low WER scores even when the speech exhibits accented characteristics.

To identify phonetic mistakes, we employ the Phoneme Error Rate (PER) as a more suitable metric than WER. PER is calculated in a manner similar to WER, focusing on phoneme errors in the transcription, rather than word-level errors.

For PER calculation, a high-quality phoneme recognition model is used, such as the one available at https://huggingface.co/facebook/wav2vec2-xlsr-53-espeak-cv-ft. The evaluation process is as follows:

- The test set is processed by the candidate AL model to produce the converted speech samples.

- These converted speech samples are fed into the phoneme recognition system to obtain the predicted phonetic transcriptions.

- PER is calculated using predicted and reference phonetic transcriptions.

This method addresses the phonetic precision of the AL model to a certain extent.

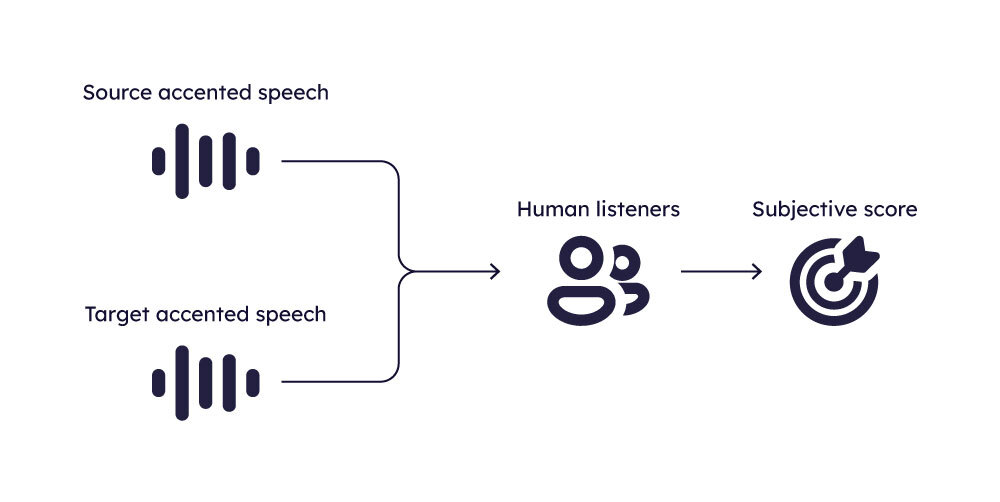

Naturalness Prediction

To assess the naturalness of generated speech, one common method involves conducting subjective listening tests. In these tests, listeners are asked to rate the speech samples on a 5-point scale, where 1 denotes very robotic speech and 5 denotes highly natural speech.

The average of these ratings, known as the Mean Opinion Score (MOS), serves as the naturalness score for the given sample.

In addition to subjective evaluations, obtaining an objective measure of speech naturalness is also feasible. It is a distinct research direction—predicting the naturalness of generated speech using AI. Models in this domain are developed using large datasets comprised of subjective listening assessments of the naturalness of generated speech (obtained from various speech-generating systems like text-to-speech, voice conversion, etc).

These models are designed to predict the MOS score for a speech sample based on its characteristics. Developing such models is a great challenge and remains an active area of research. Therefore, one should be careful when using these models to predict naturalness. Notable examples include the self-supervised learned MOS predictor and NISQA, which represent significant advances in this field.

In addition to objective metrics mentioned above, we conduct subjective listening tests and calculate objective scores using MOS predictors. We also manually examine the quality of these objective assessments. This approach enables a thorough analysis of the naturalness of our AL models, ensuring a well-rounded evaluation of their performance.

AI Accent Localization model training and inference

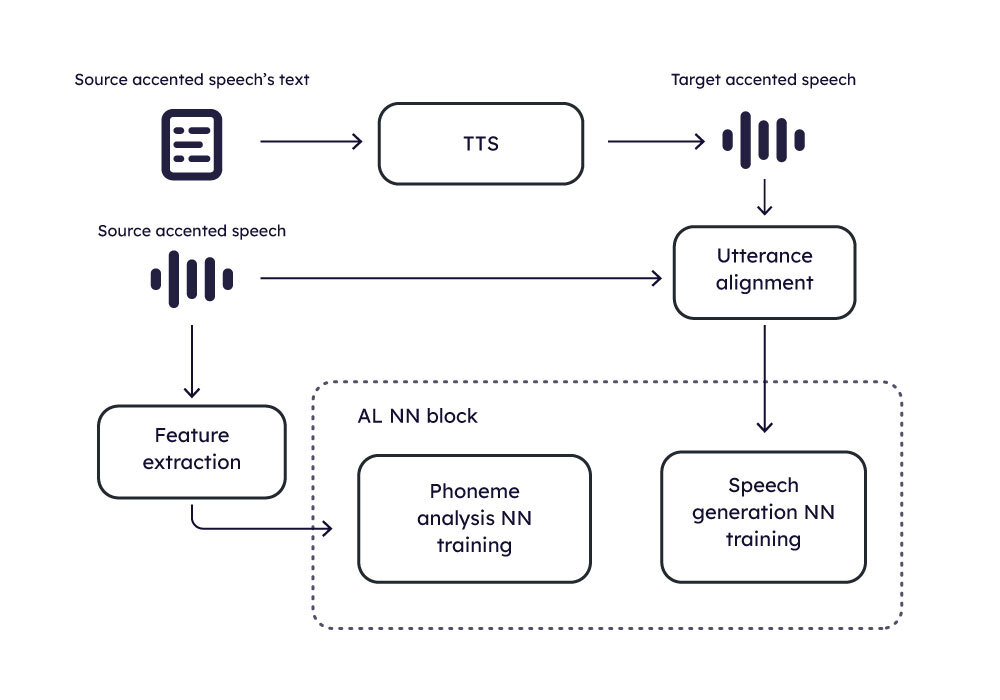

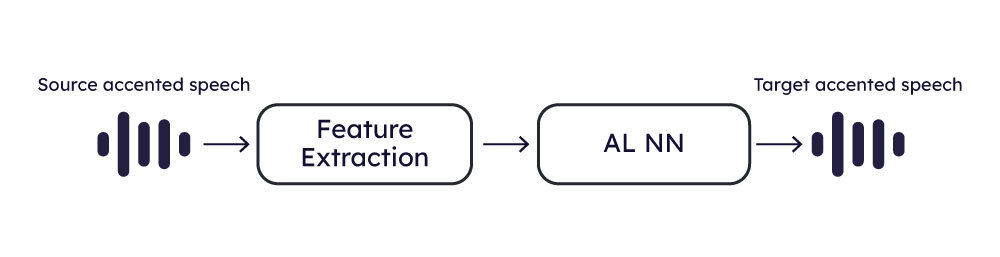

The following diagrams show how the training and inference are organized.

AI Training

AI Inference

Closing

In navigating the complexities of global call center operations, AI Accent Localization technology is a disruptive innovation, primed to bridge language barriers and elevate customer service while expanding talent pools, reducing costs, and revolutionizing CX.

References

- https://www.smartcommunications.com/resources/news/benchmark-report-2023-2/

- https://info.siteselectiongroup.com/blog/site-selection-group-releases-2023-global-call-center-location-trend-report

- https://www.siteselectiongroup.com/whitepapers

- https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE5AN37C/

The post Deep Dive: AI’s Role in Accent Localization for Call Centers appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post The Power of On-Device Transcription in Call Centers appeared first on Krisp.

]]>With advancements in Speech-to-text AI and on-device AI, the call center industry is approaching a transformative change. We should start rethinking the traditional approach of cloud-based transcriptions, bringing the process directly onto the agents’ devices.

Let’s dive into why this makes sense for modern call centers and BPOs.

- Cost Benefits: The most immediate benefit of on-device transcription is cost savings. Traditional cloud transcription services are very expensive due to the costs associated with audio data transmission and processing on remote servers. On-device transcription, however, leverages the processing power of the agent’s device, leading to a significant reduction in these costs.

- Security Enhancement: Security is a top concern in the call center world, especially when dealing with sensitive customer data. With on-device transcription, the audio is not sent to 3rd party services, drastically reducing the risk of data breaches. On-device processing aligns perfectly with stringent data protection regulations, offering peace of mind to both call centers and their customers.

- On-Device PII Redaction: This method also allows for direct PII (Personally Identifiable Information) redaction on the agent’s device. This enables call centers to use the data appropriately while adhering to customer privacy and industry regulations.

- Live Transcription: Another exciting aspect of on-device transcription is its application in providing low-latency live transcription for agents. This feature can be a game-changer, enabling agents to see a real-time transcript of the call. When integrated with existing agent-assist systems, agents can instantly receive suggestions and accurate responses, enhancing both efficiency and customer satisfaction.

- Support for all SoftPhones: Since the transcriptions and recordings are performed on the agent’s device, it can support any SoftPhone, Dialer, or CCaaS solution the call center chooses to work with, making it application-agnostic.

- Unified Experience and Storage: Many call centers (such as BPOs) must support multiple SoftPhones for their customers. With on-device transcriptions, all transcription and recording data can be saved in a unified storage giving the call center further opportunity to streamline agent experience across different communication applications and as well as easy integration with other systems.

Challenges and Solutions

The post The Power of On-Device Transcription in Call Centers appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post Speech Enhancement On The Inbound Stream: Challenges appeared first on Krisp.

]]>In today’s digital age, online communication is essential in our everyday lives. Many of us find ourselves engaged in many online meetings and telephone conversations throughout the day. Due to the nature of our work in today’s world, some find themselves having calls or attending meetings in less-than-ideal environments such as cafes, parks, or even cars. One persistent issue during our virtual interactions is the prevalence of background noise emitted from the other end of the call. This interference can lead to significant misunderstandings and disruptions, impairing comprehension of the speaker’s intended messages.

To effectively address the problem of unwanted noise in online communication, an ideal solution would involve applying noise cancellation on each user’s end, specifically on the signal captured by their microphone. This technology would effectively eliminate background sounds for each respective speaker, enhancing intelligibility and maximizing the overall online communication experience. Unfortunately, this is not the case, and not everyone has noise cancellation software, meaning they may not sound clear. This is where the inbound noise cancellation comes into play.

When delving into the topic of noise cancellation, it’s not uncommon to see terms such as speech enhancement, noise reduction, noise suppression, and speech separation used in a similar context.

In this article, we will go over the inbound speech enhancement and the main challenges applying it to online communication. But first, let’s dive in and understand the buzz and the difference between the inbound and outbound streams in the terminology of speech enhancement.

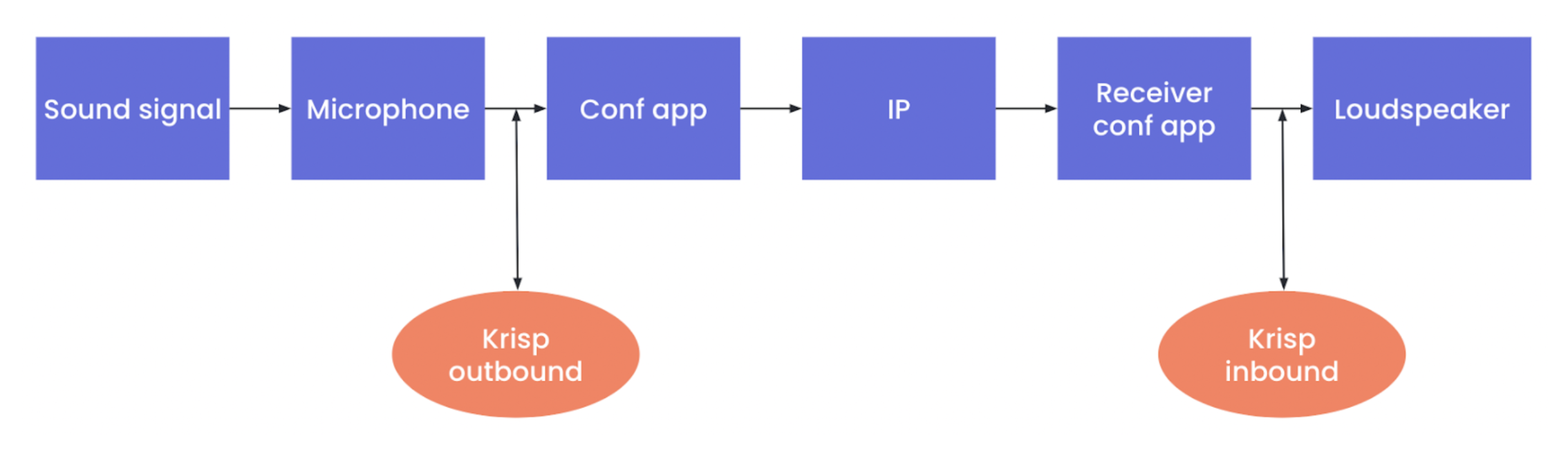

The difference in speech enhancement on the inbound and the outbound streams explained

The terms inbound and outbound we have referred to in the context of speech enhancement are basically about at which point in the communication pipeline the enhancement takes place.

Speech Enhancement On Outbound Streams

In the case of speech enhancement on the outbound stream, the algorithms are applied at the sending end after capturing the sound from the microphone but before transmitting the signal. In one of our previously published articles on Speech Enhancement, we focused mainly on the outbound use case.

Speech Enhancement On Inbound Streams

In the case of speech enhancement on the inbound stream, the algorithms are applied at the receiving end – after receiving the signal from the network but before passing it to the actual loudspeaker/headphone. Unlike outbound speech enhancement, which preserves the speaker’s voice, inbound speech enhancement has to preserve the voices of multiple speakers, all while canceling background noise.

Together, these technologies revolutionize online communication, delivering an unparalleled experience for users around the world.

The challenges of applying speech enhancement in online communication

Online communication is a diverse landscape, encompassing a wide array of scenarios, devices, and network conditions. As we strive to enhance the quality of audio in both outbound and inbound communication, we encounter several challenges that transcend these two realms.

Wide Range of Devices Support

Online communication takes place across an extensive spectrum of devices. The microphones in those devices range from built-in laptop microphones to high-end headphones, webcams with integrated microphones, and external microphone setups. Each of these microphones may have varying levels of quality and sensitivity. Ensuring that speech enhancement algorithms can adapt to and optimize audio quality across this device spectrum is a significant challenge. Moreover, the user experience should remain consistent regardless of the hardware in use.

Wide Range of Bandwidths Support

One critical aspect of audio quality is the signal bandwidth. Different devices and audio setups may capture and transmit audio at varying signal bandwidths. Some may capture a broad range of frequencies, while others may have limited bandwidth. Speech enhancement algorithms must be capable of processing audio signals across this spectrum efficiently. This includes preserving the essential components of the audio signal while adapting to the limitations or capabilities of the particular bandwidth, ensuring that audio quality remains as high as possible.

Strict CPU Limitations

Online communication is accessible to a broad audience, including individuals with low-end PCs or devices with limited processing power. Balancing the demand for advanced speech enhancement with these strict CPU limitations is a delicate task. Engineers must create algorithms that are both computationally efficient and capable of running smoothly on a range of hardware configurations.

Large Variety of Noises Support

Background noise in online communication can vary from simple constant noise, like the hum of an air conditioner, to complex and rapidly changing noises. Speech enhancement algorithms must be robust enough to identify and suppress a wide variety of noise sources effectively. This includes distinguishing between speech and non-speech sounds, as well as addressing challenges posed by non-stationary noises, such as music or babble noise.

The challenges specific to inbound speech enhancement

As we have discussed, Inbound speech enhancement may be a critical component of online communication, focusing on improving the quality of audio received by users. However, this task comes with its own set of intricate challenges that demand innovative solutions. Here, we delve into the unique challenges faced when enhancing incoming audio streams.

Multiple Speakers’ Overlapping Speech Support

One of the foremost challenges in inbound speech enhancement is dealing with multiple speakers whose voices overlap. In scenarios like group video calls or virtual meetings, participants may speak simultaneously, making it challenging to distinguish individual voices. Effective inbound speech enhancement algorithms must not only reduce background noise but also keep the overlapping speech untouched, ensuring that every participant’s voice is clear and discernible to the listener.

Diversity of Users’ Microphones

Online communication accommodates an extensive range of devices from different speakers. Users may connect via mobile phones, car audio systems, landline phones, or a multitude of other devices. Each of these devices can have distinct characteristics, microphone quality, and signal processing capabilities. Ensuring that inbound speech enhancement works seamlessly across this diverse array of devices is a complex challenge that requires robust adaptability and optimization.

Wide Variety of Audio Codecs Support

Audio codecs are used to compress and transmit audio data efficiently over the internet. However, different conferencing applications and devices may employ various audio codecs, each with its own compression techniques and quality levels. Inbound speech enhancement must be codec-agnostic, capable of processing audio streams regardless of the codec in use, to ensure consistently high audio quality for users.

Software Processing of Various Conferencing Applications Support

Online communication occurs through a multitude of conferencing applications, each with its unique software processing and audio transmission methods. Optimally, inbound speech enhancement should be engineered to seamlessly integrate with any of these diverse applications while maintaining an uncompromised level of audio quality. This requirement is independent of any audio processing technique utilized in the application. These processes can span a wide spectrum from automatic gain control to proprietary noise cancellation solutions, each potentially introducing different levels and types of audio degradation.

Internet Issues and Lost Packets Support

Internet connectivity is prone to disruptions, leading to variable network conditions and packet loss. Inbound speech enhancement faces the challenge of coping with these issues gracefully. The algorithm must be capable of maintaining the audio quality in case of lost audio packets. The ideal solution would even be able to mitigate the damage caused by poor networks by advanced Packet Loss Concealment algorithms.

How to face Inbound use case challenges?

As mentioned in the Speech Enhancement blog post, to create a high-quality speech enhancement model, one needs to apply deep learning methods. Moreover, in the case of inbound speech enhancement, we need to apply more diverse data augmentation reflecting real-life scenarios of inbound use cases to obtain high-quality training data for the deep learning model. Now, let’s delve into some data augmentations specific to inbound scenarios

Modeling of multiple speaker calls

In the quest for an effective solution to inbound speech enhancement, one crucial aspect is the modeling of multi-speaker and multi-noise scenarios. In an ideal approach, the system employs sophisticated audio augmentation techniques to generate audio mixes (see the previous article) that consist of multiple voice and noise sources. These sources are thoughtfully designed to simulate real-world scenarios, particularly those involving multiple speakers speaking concurrently, common in virtual meetings and webinars.

Through meticulous modeling, each audio source is imbued with distinct acoustic characteristics, capturing the essence of different environments and devices. These scenarios are carefully crafted to represent the challenges of online communication, where users encounter a dynamic soundscape. By training the system with these diverse multi-speaker and multi-noise mixes, it gains the capability to adeptly distinguish individual voices and suppress background noise.

Modeling of diverse acoustic conditions

Building inbound speech enhancement requires more than just understanding the mix of voices and noise; it also involves accurately representing the acoustic properties of different environments. In the suggested solution, this is achieved through Room Impulse Response (RIR) and Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) modeling.

RIR modeling involves applying filters to mimic the way sound reflects and propagates in a room environment. These filters capture the unique audio characteristics of different environments, from small meeting rooms to bustling cafes. Simultaneously, IIR filters are meticulously designed to match the specific characteristics of different microphones, replicating their distinct audio signatures. By applying these filters, the system ensures that audio enhancement remains realistic and adaptable across a wide range of settings, further elevating the inbound communication experience.

Versatility Through Codec Adaptability

An essential aspect of an ideal solution for inbound speech enhancement is versatility in codec support. In online communication, various conferencing applications employ a range of audio codecs for data compression and transmission. These codecs can vary significantly in terms of compression efficiency and audio quality, from enterprise-specific VOIP codecs like G.711 and G.729 to high-end solutions such as OPUS and SILK.

To offer an optimal experience, the solution should be codec-agnostic, capable of seamlessly processing audio streams regardless of the codec in use. To meet this goal, we need to pass raw audio signals to various audio codecs as the codec augmentation of training data.

Summary

Inbound speech enhancement refers to the software processing that occurs at the listener’s end in online communication. This task comes with several challenges, including handling multiple speakers in the same audio stream, adapting to diverse acoustic environments, and accommodating various devices and software preferences used by users. In this discussion, we explored a series of augmentations that can be integrated into a neural network training pipeline to address these challenges and offer an optimal solution.

Try next-level audio and voice technologies

Krisp licenses its SDKs to embed directly into applications and devices. Learn more about Krisp’s SDKs and begin your evaluation today.

References

- Speech Enhancement Review: Krisp Use Case. Krisp Engineering Blog

- Microphones. Wiley Telecom

- Bandwidth (signal processing). Wikipedia

- Babble Noise: Modeling, Analysis, and Applications. Nitish KrishnamurthyJohn H. L. Hansen

- Audio codec. Wikipedia

- Deep Noise Suppression (DNS) Challenge: Datasets

- Can You Hear a Room?. Krisp Engineering Blog

- Infinite impulse response. Wikipedia

- Pulse code modulation (PCM) of voice frequencies. ITU-T Recommendations

- Coding of speech at 8 kbit/s using conjugate-structure algebraic-code-excited linear prediction (CS-ACELP). ITU-T Recommendations

- Opus Interactive Audio Codec

- SILK codec(v1.0.9). Ploverlake

The article is written by:

- Ruben Hasratyan, MBA, BSc in Physics, Staff ML Engineer, Tech Lead

- Stepan Sargsyan, PhD in Mathematical Analysis, ML Architect, Tech Lead

The post Speech Enhancement On The Inbound Stream: Challenges appeared first on Krisp.

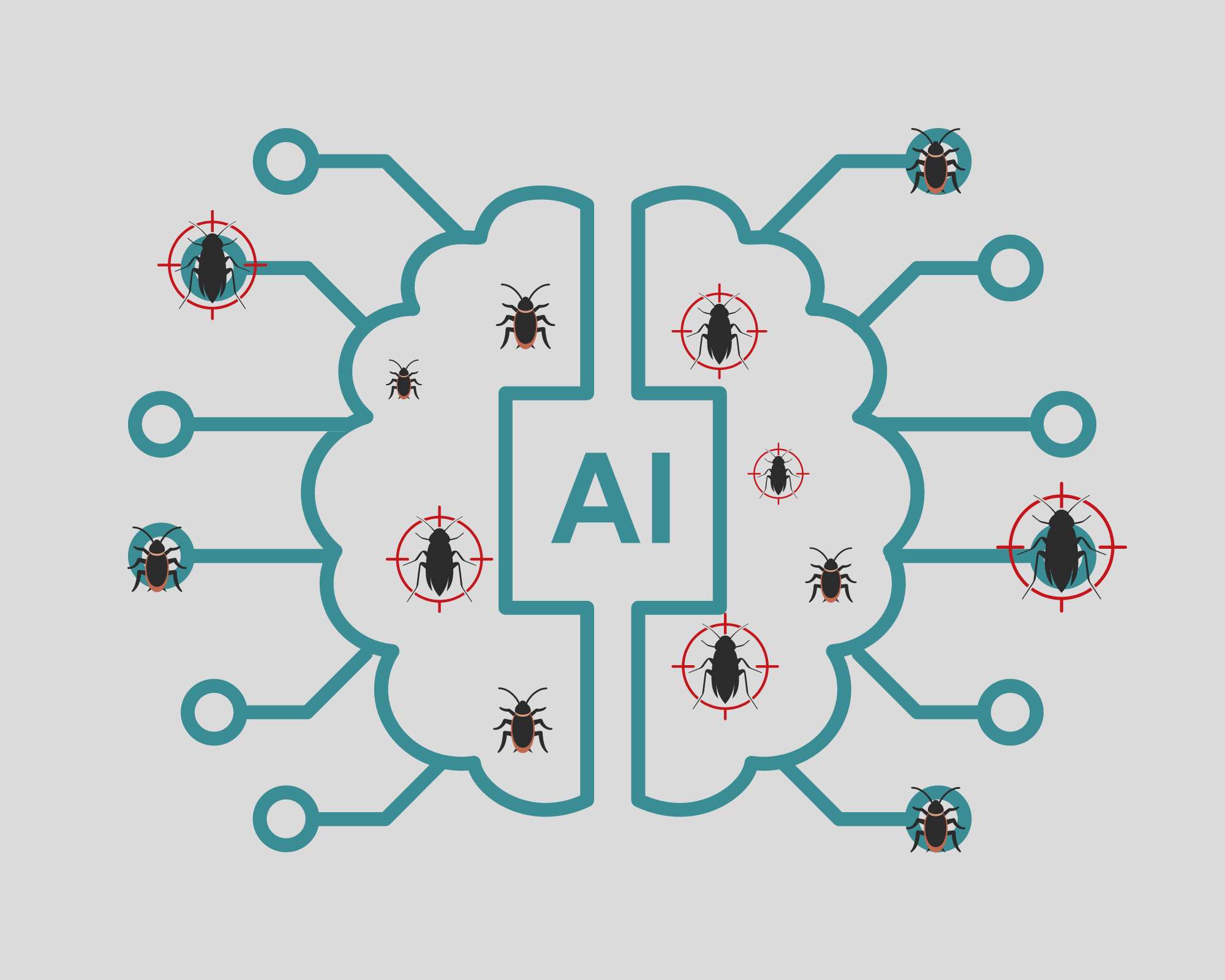

]]>The post Applying the Seven Testing Principles to AI Testing appeared first on Krisp.

]]>With the constant growth of artificial intelligence, numerous algorithms and products are being introduced into the market on a daily basis, each with its unique functionality in various fields. Like software systems, AI systems also have their distinct lifecycle, and quality testing is a critical component of it. However, in contrast to software systems, where quality testing is focused on verifying the desired behavior generated by the logic, the primary objective in AI system quality testing is to ensure that the logic is in line with the expected behavior. Hence, the testing object in AI systems is the logic itself rather than the desired behavior. Also, unlike traditional software systems, AI systems necessitate careful consideration of tradeoffs, such as the delicate balance between overall accuracy and CPU usage.

Despite their differences, the seven principles of software testing outlined by ISTQB (International Software Testing Qualifications Board) can be easily applied to AI systems. This article will examine each principle in-depth and explore its correlation with the testing of AI systems. We will base this exposition on Krisp’s Voice Processing algorithms, which incorporate a family of pioneering technologies aimed at enhancing voice communication. Each of Krisp’s voice-related algorithms, based on machine learning paradigms, is amenable to the general testing principles we discuss below. However, for the sake of illustration and as our reference point, we will use Krisp’s Noise Cancellation technology (referred to as NC). This technology is based on a cutting-edge algorithm that operates on the device in real-time and is renowned for its ability to enhance the audio and video call experience by effectively eliminating disruptive background noises. The algorithm’s efficacy can be influenced by diverse factors, including usage conditions, environments, device specifications, and encountered scenarios. Rigorous testing of all these parameters becomes indispensable, accomplished by employing a diverse range of test datasets and conducting both subjective and objective evaluations. Therefore, it is crucial to test all these parameters, while keeping in mind the seven testing principles both,

1. Testing shows the presence of defects, not their absence

This principle underscores that despite the effort invested in finding and fixing errors in software, it cannot guarantee that the product will be entirely defect-free. Even after comprehensive testing, defects can still persist in the system. Hence, it is crucial to continually test and refine the system to minimize the risk of defects that may cause harm to users or the organization.

This is particularly significant in the context of AI systems, as AI algorithms are in general not expected to achieve 100% accuracy. For instance, testing may reveal that an underlying AI-based algorithm, such as the NC algorithm, has issues when canceling out white noises. Even after addressing the problem for observed scenarios and improving accuracy, there is no guarantee that the issue will never resurface in other environments and be detected by users. Testing only serves to reduce the likelihood of such occurrences.

2. Exhaustive testing is impossible

The second testing principle highlights that achieving complete test coverage by testing every possible combination of inputs, preconditions, and environmental factors is not feasible. This challenge is even more profound in AI systems since the number of possible combinations that the algorithm needs to cover is often infinite.

For instance, in the case of the NC algorithm, testing every microphone device, in every condition, with every existing noise type would be an endless endeavor. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize testing based on risk analysis and business objectives. For example, testing should focus on ensuring that the algorithm does not cause voice cutouts with the most popular office microphone devices in typical office conditions.

By prioritizing testing activities based on identified risks and critical functionalities, testing efforts can be optimized to ensure that the most important defects are detected and addressed first. This approach helps to balance the need for thorough testing with the practical realities of finite time, resources, and costs associated with testing.

3. Early testing saves time and money

This principle emphasizes the importance of conducting testing activities as early as possible in the development lifecycle, including AI products. Early testing is a cost-effective approach to identifying and resolving defects in the initial phases, reducing expenses and time, whereas detecting errors at the last minute can be the most expensive to rectify.

Ideally, testing should start during the algorithm’s research phase, way before it becomes an actual product. This can help to identify possible undesirable behavior and prevent it from propagating to the later stages. This is especially crucial since the AI algorithm training process can take weeks if not months. Detecting errors in the late stages can lead to significant release delays, impacting the project’s timeline and budget.

Testing the algorithm’s initial experimental version can help to identify stability concerns and reveal any limitations that require further refinement. Furthermore, early testing helps to validate whether the selected solution and research direction are appropriate for addressing the problem at hand. Additionally, analyzing and detecting patterns in the algorithm’s behavior assists in gaining insights into the research trajectory and potential issues that may arise.

In the context of the NC project, early testing can help to evaluate whether the algorithm works steadily when subjected to different scenarios, such as retaining considerable noise after a prolonged period of silence. Finding and addressing such patterns at an early stage ensures smoother and more efficient resolution.

4. Defects cluster together

The principle of defect clustering suggests that software defects and errors are not distributed randomly but instead tend to cluster or aggregate in certain areas or components of the system. This means that if multiple errors are found in a specific area of the software, it is highly likely that there are more defects lurking in that same region. This principle also applies to AI systems, where the discovery of logically undesired behavior is a red flag that future tests will likely uncover similar issues.

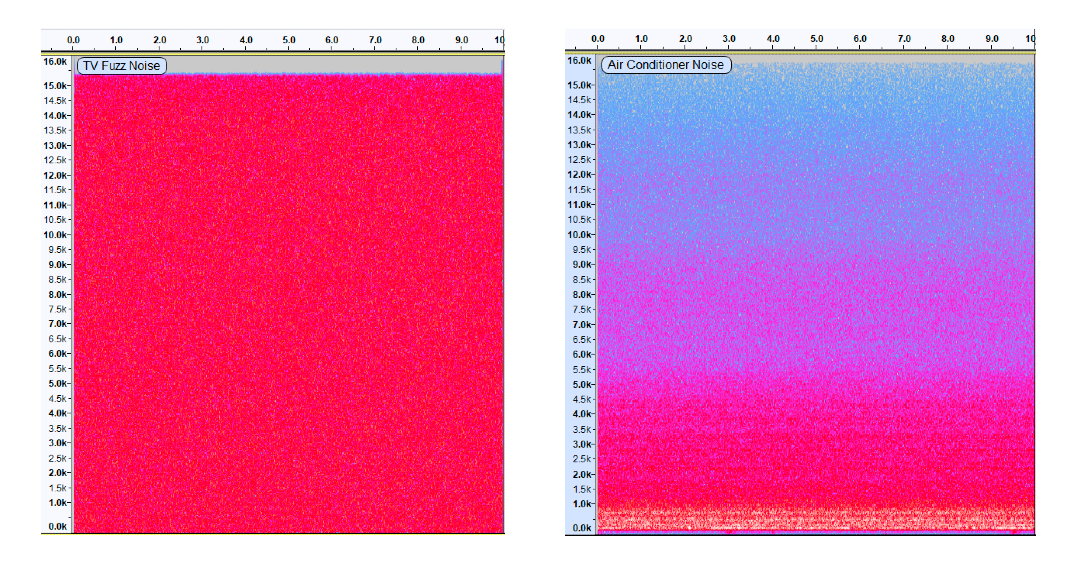

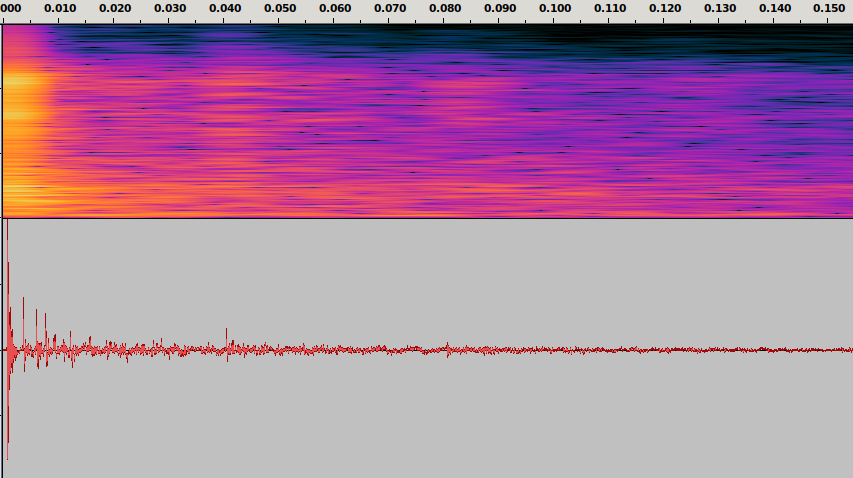

For example, suppose a noise cancellation algorithm struggles to cancel TV fuzz noise when presented alongside speech. In that case, further tests may reveal the same problem when the algorithm is faced with background noise from an air conditioner. Although both noises may seem alike, careful observation of the frequency visual representation (Spectrogram) clearly highlights the noticeable distinction.

TV Fuzz Noise

AC Noise

Credits: https://www.youtube.com/

Identifying high-risk areas that could potentially damage user experience is another way that the principle of defect clustering can be beneficial. During the testing process, these areas can be given top priority. Using the same noise cancellation algorithm as an example, the highest-risk area is the user’s speech quality, and voice-cutting issues are considered the most critical defects. If the algorithm exhibits voice-cutting behavior in one scenario, it is possible that it may also cause voice degradation in other scenarios.

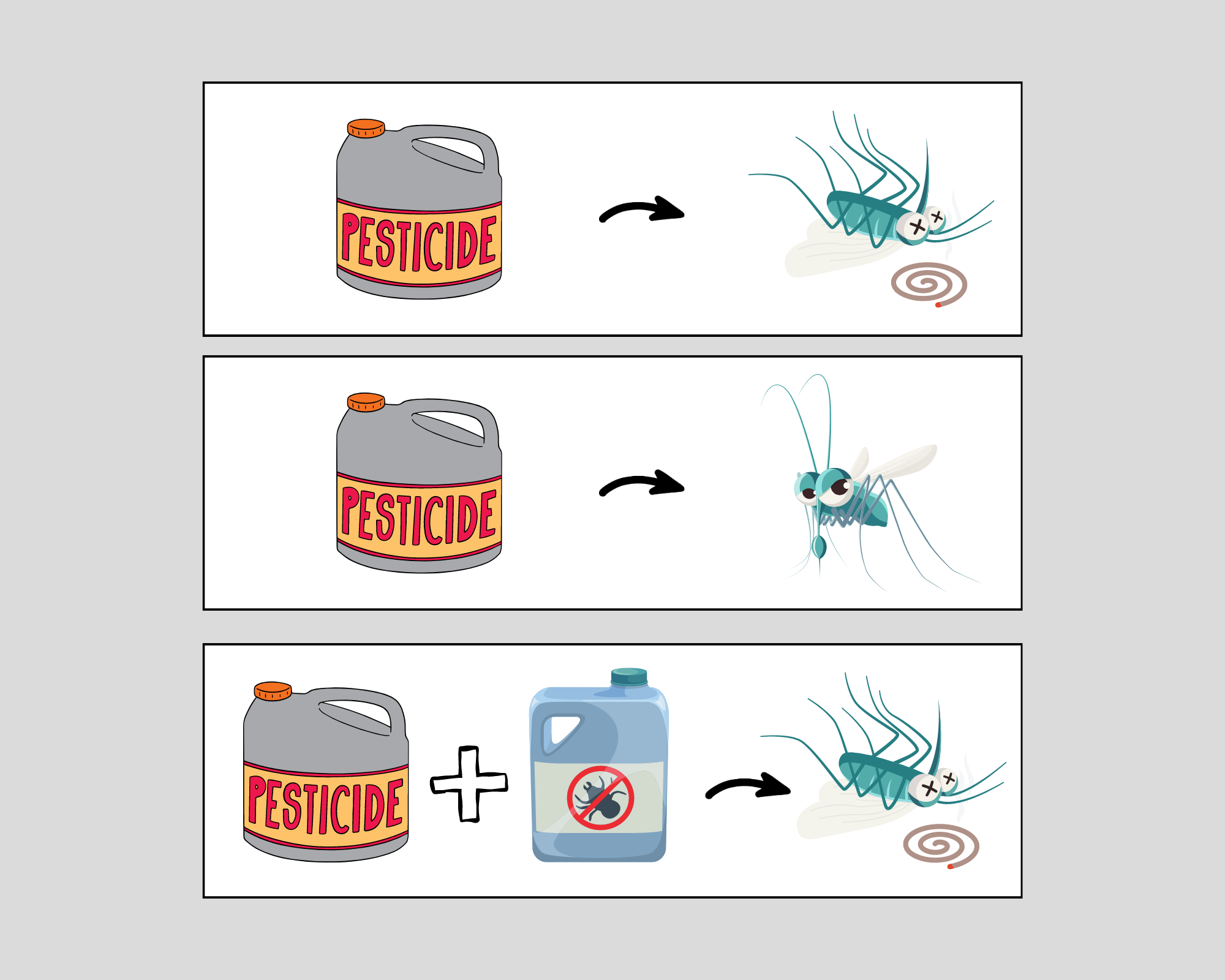

5. Beware of the pesticide paradox

The pesticide paradox is a well-known phenomenon in pest control, where applying the same pesticide to pests can lead to immunity and resistance. The same principle applies to software and AI testing, where the “pesticide” is testing, and the “pests” are software bugs. Running the same set of tests repeatedly may lead to the diminishing effectiveness of those tests as both AI and software systems adapt and become immune to them.

To avoid the pesticide paradox in software and AI testing, it’s essential to use a range of testing techniques and tools and to update tests regularly. When existing test cases no longer reveal new defects, it’s time to implement new cases or incorporate new techniques and tools.

Similarly, AI systems must be constantly monitored for the pesticide paradox, known as “overfitting.” Although practically an AI system can never be entirely free of bugs, it’s essential to update test datasets and cases, and possibly introduce new metrics or tools, once the system can easily handle existing tests.

Take the example of a noise cancellation algorithm that initially worked almost flawlessly on audios with low-intensity noise. To enhance the algorithm’s quality and discover new bugs, new datasets were created, featuring higher-intensity noises that reached speech loudness.

By avoiding the pesticide paradox in both software and AI testing, we can protect our systems and ensure they remain effective in their respective fields.

6. Testing is context dependent

Testing methods must be tailored to the specific context in which they will be implemented. This means that testing is always context-dependent, with each software or AI system requiring unique testing approaches, techniques, and tools.

In the realm of AI, the context includes a range of factors, such as the system’s purpose, the characteristics of the user base, whether the system operates in real-time or not, and the technologies utilized.

Context is of paramount importance when it comes to developing an effective testing strategy, techniques, and tools for the NC algorithms. Part of this context involves understanding the needs of the users, which can assist in selecting appropriate testing tools such as microphone devices. As a result, an understanding of context enables the reproduction and testing of users’ real-life scenarios.

By considering context, it becomes possible to create better-designed tests that accurately represent actual use cases, leading to more reliable and accurate results. Ultimately, this approach can ensure that testing is more closely aligned with real-world situations, increasing the overall effectiveness and utility of the NC algorithm.

7. Absence-of-errors is a fallacy

The notion that the absence of errors can be achieved through complete test coverage is a fallacy. In some cases, there may be unrealistic expectations that every possible test should be run and every potential case should be checked. However, the principles of testing remind us that achieving complete test coverage is practically impossible. Moreover, it is incorrect to assume that complete test coverage guarantees the success of the system. For example, the system may function flawlessly but still be difficult to use and fail to meet the needs and requirements of users from the product perspective. This also applies to AI systems as well.

Consider, for instance, the NC algorithm, which may have excellent quality, cancel out noise and maintain speech clarity, making it virtually free of defects. However, it being too complex and large, may render it useless as a product.

Conclusion

To sum up, AI systems have unique lifecycles and require a different approach to testing from traditional software systems. Nevertheless, the seven principles of software testing outlined by the ISTQB can be applied to AI systems. Applying these principles can help identify critical defects, prioritize testing efforts, and optimize testing activities to ensure that the most important defects are detected and addressed first. All Krisp’s algorithms have demonstrated that adhering to these rules leads to improved accuracy, higher quality, and increased reliability and safety of the AI system in various fields.

Try next-level audio and voice technologies

Krisp licenses its SDKs to embed directly into applications and devices. Learn more about Krisp’s SDKs and begin your evaluation today.

References

The article is written by:

- Tatevik Yeghiazaryan, BSc in Software Engineering, Senior QA Engineer

The post Applying the Seven Testing Principles to AI Testing appeared first on Krisp.

]]>The post Can You Hear a Room? appeared first on Krisp.

]]>Sound propagation has distinctive features associated with the environment where it happens. Human ears can often clearly distinguish whether a given sound recording was produced in a small room, large room, or outdoors. One can even get a sense of a direction or a distance from the sound source by listening to a recording. These characteristics are defined by the objects around the listener or a recording microphone such as the size and material of walls in a room, furniture, people, etc. Every object has its own sound reflection, absorption, and diffraction properties, and all of them together define the way a sound propagates, reflects, attenuates, and reaches the listener.

In acoustic signal processing, one often needs a way to model the sound field in a room with certain characteristics, in order to reproduce a sound in that specific setting, so to speak. Of course, one could simply go to that room, reproduce the required sound and record it with a microphone. However, in many cases, this is inconvenient or even infeasible.

For example, suppose we want to build a Deep Neural Net (DNN)-based voice assistant in a device with a microphone that receives pre-defined voice commands and performs actions accordingly. We need to make our DNN model robust to various room conditions. To this end, we could arrange many rooms with various conditions, reproduce/record our commands in those rooms, and feed the obtained data to our model. Now, if we decide to add a new command, we would have to do all this work once again. Other examples are Virtual Reality (VR) applications or architectural planning of buildings where we need to model the acoustic environment in places that simply do not exist in reality.

In the case of our voice assistant, it would be beneficial to be able to encode and digitally record the acoustic properties of a room in some way so that we could take any sound recording and “embed” it in the room by using the room “encoding”. This would free us from physically accessing the room every time we need it. In the case of VR or architectural planning applications, the goal then would be to digitally generate a room’s encoding only based on its desired physical dimensions and the materials and objects contained in it.

Thus, we are looking for a way to capture the acoustic properties of a room in a digital record, so that we can reproduce any given audio recording as if it was played in that room. This would be a digital acoustic model of the room representing its geometry, materials, and other things that make us “hear a room” in a certain sense.

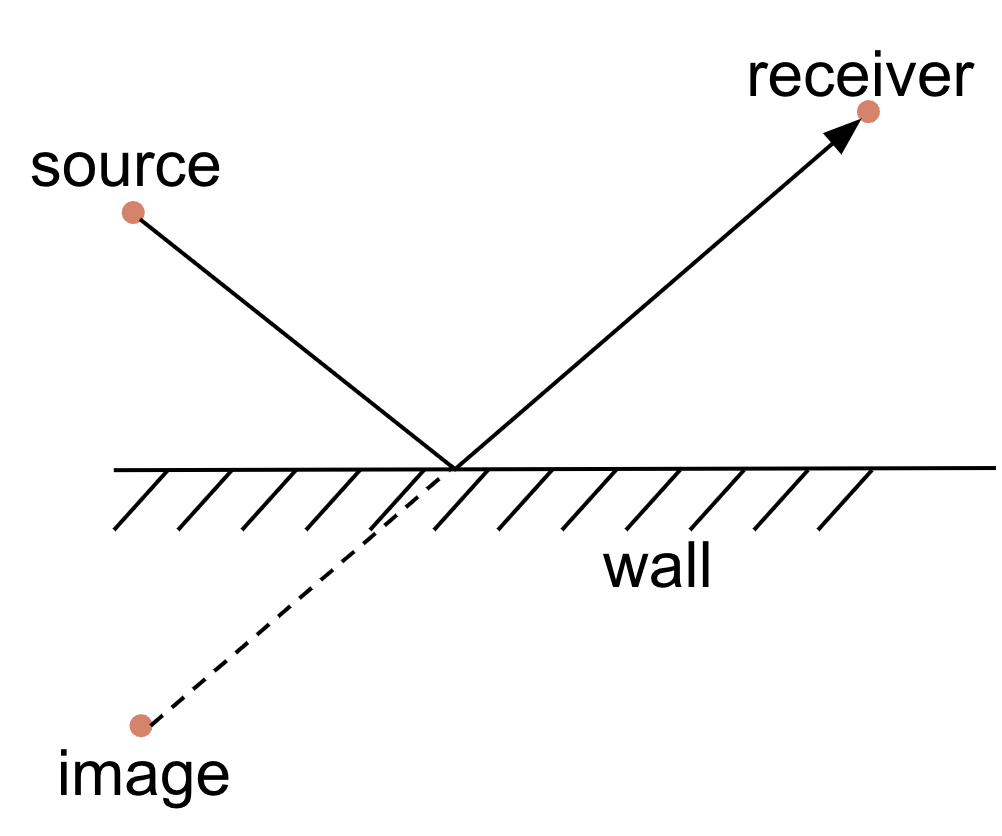

What is RIR?

Room impulse response (RIR for short) is something that does capture room acoustics, to a large extent. A room with a given sound source and a receiver can be thought of as a black-box system. Upon receiving on its input a sound signal emitted by the source, the system transforms it and outputs whatever is received at the receiver. The transformation corresponds to the reflections, scattering, diffraction, attenuation and other effects that the signal undergoes before reaching the receiver. Impulse response describes such systems under the assumption of time-invariance and linearity. In the case of RIR, time-invariance means that the room is in a steady state, i.e, the acoustic conditions do not change over time. For example, a room with people moving around, or a room where the outside noise can be heard, is not time invariant since the acoustic conditions change with time. Linearity means that if the input signal is a scaled superposition of two other signals, x and y, then the output signal is a similarly scaled superposition of the output signals corresponding to x and y, individually. Linearity holds with sufficient fidelity in most practical acoustic environments (while time-invariance can be achieved in a controlled environment).

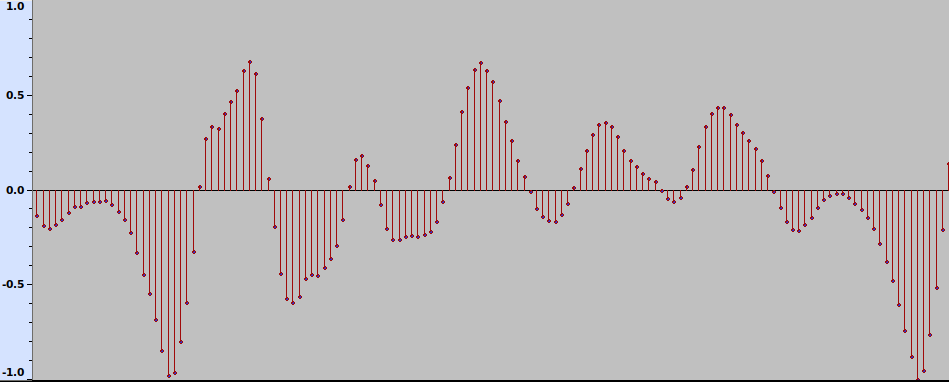

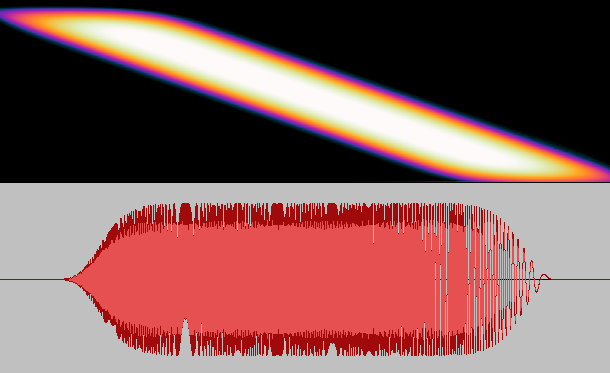

Let us take a digital approximation of a sound signal. It is a sequence of discrete samples, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 The waveform of a sound signal.

Each sample is a positive or negative number that corresponds to the degree of instantaneous excitation of the sound source, e.g., a loudspeaker membrane, as measured at discrete time steps. It can be viewed as an extremely short sound, or an impulse. The signal can thus be approximately viewed as a sequence of scaled impulses. Now, given time-invariance and linearity of the system, some mathematics shows that the effect of a room-source-receiver system on an audio signal can be completely described by its effect on a single impulse, which is usually referred to as an impulse response. More concretely, impulse response is a function h(t) of time t > 0 (response to a unit impulse at time t = 0) such that for an input sound signal x(t), the system’s output is given by the convolution between the input and the impulse response. This is a mathematical operation that, informally speaking, produces a weighted sum of the delayed versions of the input signal where weights are defined by the impulse response. This reflects the intuitive fact that the received signal at time t is a combination of delayed and attenuated values of the original signal up to time t, corresponding to reflections from walls and other objects, as well as scattering, attenuation and other acoustic effects.

For example, in the recordings below, one can see the RIR recorded by a clapping sound (see below), an anechoic recording of singing, and their convolution.

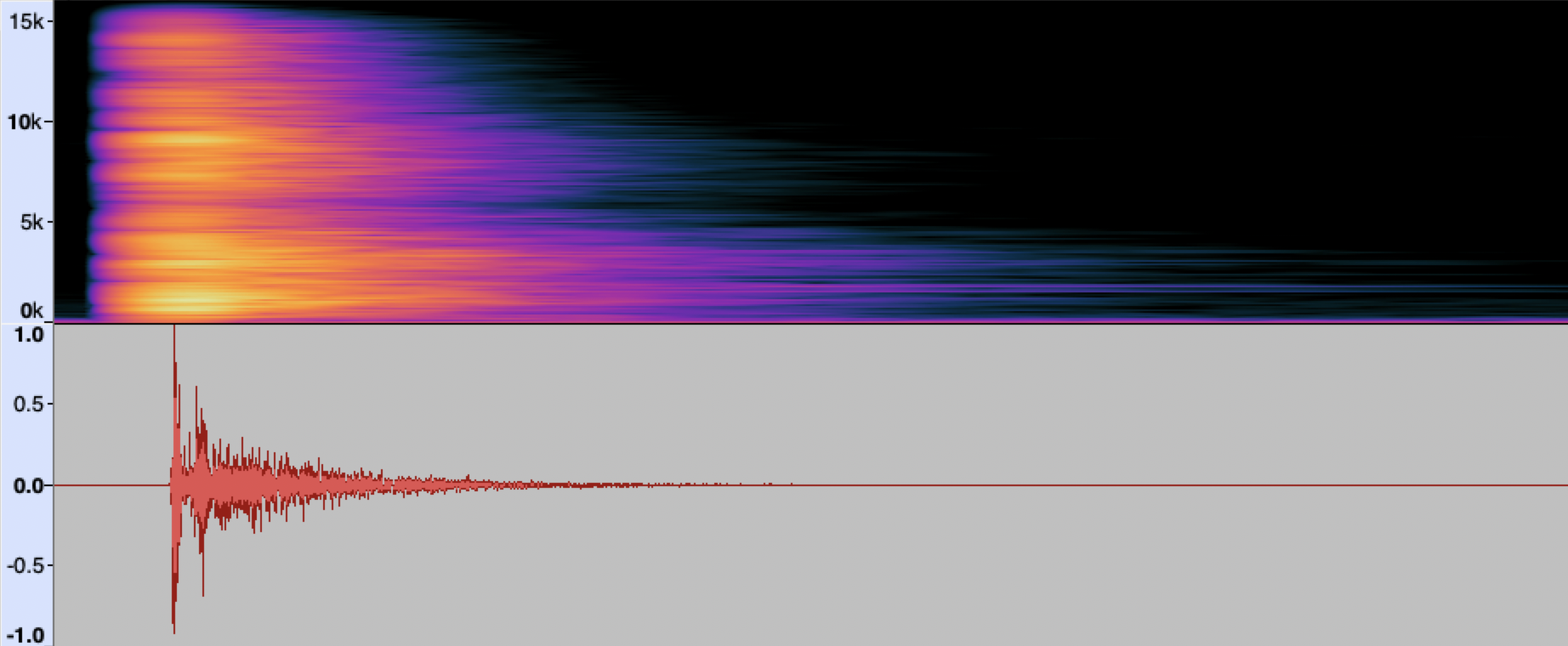

RIR

Singing anechoic

Singing with RIR

It is often useful to consider sound signals in the frequency domain, as opposed to the time domain. It is known from Fourier analysis that every well-behaved periodic function can be expressed as a sum (infinite, in general) of scaled sinusoids. The sequence of the (complex) coefficients of sinusoids within the sum, the Fourier coefficients, provides another, yet equivalent representation of the function. In other words, a sound signal can be viewed as a superposition of sinusoidal sound waves or tones of different frequencies, and the Fourier coefficients show the contribution of each frequency in the signal. For finite sequences such as digital audio, that are of practical interest, such decompositions into periodic waves can be efficiently computed via the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).

For non-stationary signals such as speech and music, it is more instructive to do analysis using the short-time Fourier transform (STFT). Here, we split the signal into short equal-length segments and compute the Fourier transform for each segment. This shows how the frequency content of the signal evolves with time (see Fig. 2). That is, while the signal waveform and Fourier transform give us only time and only frequency information about the signal (although one being recoverable from another), the STFT provides something in between.

Fig. 2 Spectrogram of a speech signal.

A visual representation of an STFT, such as the one in Fig. 2, is called a spectrogram. The horizontal and vertical axes show time and frequency, respectively, while the color intensity represents the magnitude of the corresponding Fourier coefficient on a logarithmic scale (the brighter the color, the larger is the magnitude of the frequency at the given time).

Measurement and Structure of RIR

In theory, the impulse response of a system can be measured by feeding it a unit impulse and recording whatever comes at the output with a microphone. Still, in practice, we cannot produce an instantaneous and powerful audio signal. Instead, one could record RIR approximately by using short impulsive sounds. One could use a clapping sound, a starter gun, a balloon popping sound, or the sound of an electric spark discharge.

Fig. 3 The spectrogram and waveform of a RIR produced by a clapping sound.

The results of such measurements (see, for example, Fig. 3) may be not sufficiently accurate for a particular application, due to the error introduced by the structure of the input signal. An ideal impulse, in some mathematical sense, has a flat spectrum, that is, it contains all frequencies with equal magnitude. The impulsive sounds above usually significantly deviate from this property. Measurements with such signals may also be poorly reproducible. Alternatively, a digitally created impulsive sound with desired characteristics could be played with a loudspeaker, but the power of the signal would still be limited by speaker characteristics. Among other limitations of measurements with impulsive sounds are: particular sensitivity to external noise (from outside the room), sensitivity to nonlinear effects of the recording microphone or emitting speaker, and the directionality of the sound source.